Image courtesy of the author.

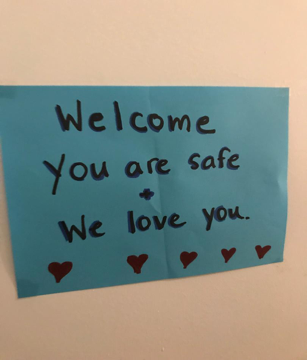

I returned recently from El Paso, so much in the news lately. There is an emergency at the border, but not the one trumpeted from the White House. The emergency at the border is the emergency faced by so many suffering human beings fleeing violence and poverty, desperately seeking refuge. It is the emergency faced by those who believe that America still stands behind the words of a Jewish poet emblazoned on the Statue of Liberty, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free….” It is the emergency faced by all of the caring and righteous people who are doing their utmost to help those who suffer. My mind is flooded with images that come on a flow of tears. My heart is breaking from what I saw in just a few days, traveling to witness and to bear witness with T’ruah, the rabbinic call for human rights, and HIAS, the venerable organization that was founded to help Jewish refugees when no one else would, now an organization that is acting from that memory to help all refugees.

I returned feeling overwhelmed and exhausted, wondering at the physical, emotional, and moral stamina of those who work with migrants every day. Images and vignettes come to me, fragments of thoughts that swirl, some telling of the heartache and some of the hope. In the brokenness of my heart there is a silent space from which I seek to hold and to hope, to search out the ways in which we are called to act in response to a moral emergency.

In the way of the Haggadah, as the rabbis taught, we begin the telling from a place of shame and move toward the praiseworthy, matchil big’nut u’m’sayem b’shevach (Mishna P’sachim 10:4). So we began with a visit to the Otero County Processing Center, a place of shame, a privately contracted prison in New Mexico. The very idea is scandalous and revolting, that a corporation is profiting from the misery of human beings. We were led on a tour of the prison by the warden herself, along with a chaplain and an ICE agent, all clearly wanting to show us how well they do in caring for those incarcerated there, clearly wanting to show their professionalism. We could see men in chains being processed. The warden simply opened the door to dormitory rooms, no knock, of course, no regard for the dignity of those inside. Before leaving one room, I asked the warden to please say in Spanish to the men we had intruded upon that we thank them. She looked at me quizzically, but she did say it to them. We waved to the men we passed, giving thumbs up. I tried to make eye contact with as many as I could, touching my heart, extending my hand. The motto of Otero is “BIONIC,” for “Believe It Or Not, I Care.” I don’t believe it, not for a moment. I was filled with the awful sense of Hannah Arendt’s description of the work done for the Nazi state by “good Germans,” the banality of evil. Hardly a new question, I wondered about those who carry out the cruel policies, the jailers, the judges, the border guards. I wondered how they sleep at night, how they hug their own children. I wondered how buried within themselves is the spark of their own goodness that waits to be called forth.

We saw among these ordinary people, presumably otherwise good people, an amorphous allegiance to the state that blinds eyes and heart to the desperate needs of human beings standing before their very eyes, placed by circumstance into their control. At the same time, in its cynical manipulation of language and policy, referring to “illegal” migrants, illegally moving U.S. border guards onto Mexican soil, we saw how the government itself shows no allegiance to the very laws that are meant to reflect the more humane principles upon which this country’s moral survival depends. I thought often of the challenge set forth by Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (19th century Germany) in his Torah commentary to Exodus chapter 23, verse 9 on the Torah’s oft repeated exhortation not to mistreat or oppress the stranger: “The treatment accorded by a state to the aliens living within its jurisdiction is the most accurate indication of the extent to which justice and humanity prevail in that state.”

Approaching Passover, I thought again, and so many times over, of the Haggadah, of our own story of suffering and liberation, of a desert journey to freedom. I thought of the suffering visited upon children in the story, of the children in the Haggadah, of our own children at the Seder table, as we visited a privately run children’s home. There seemed to be a genuine sense of caring for the children among the staff, but how to balance caring and the policies that have resulted in the incarceration of children, children without their parents, trauma on their faces, not free to leave, not free to be children? I keep seeing the face of one child, a boy of fourteen sitting in the back of a classroom, soft, shy eyes; short, curly black hair, an unformed question on his lightly pursed lips, as though asking so many more than four questions, why, a hundred times, why? As I try to hold this child’s face, it merges and becomes one for me with the face of a Holocaust child that stares at me weekly from a page in a small book of Shabbos table songs and blessings. I imagined his longing for his parents, of his parents’ longing for him. I wondered, as he must, of their whereabouts; wondering if and when they shall be reunited. I wondered if he would be for me this year the simple child or the child who does not know how to ask.

Image courtesy of the author.

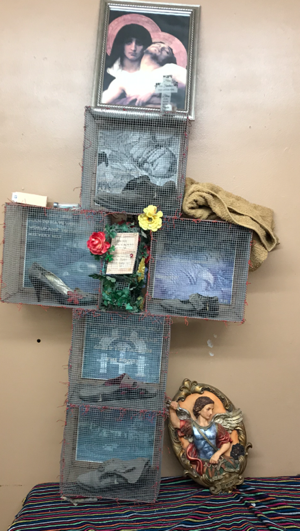

Turning the hearts of the parents to the children and of the children to the parents, Elijah’s presence at the Seder tells of the ultimate turning, the flowering of a world filled with peace and justice. In the journey from the shameful to the praiseworthy, we encountered some of the most righteous people I have ever met, people who are doing the work of Elijah. With little time to ask of why or when, they do all in their human power to lovingly assist the thousands upon thousands of people who come seeking asylum, seeking shelter, most of whom will never find a place in America to call home, but who now need a roof, a bed, food, and comfort. The finest of Catholic faith is expressed by these saints, by these people who struggle daily to meet overwhelming human needs. We would call them tzadikim/the righteous ones, people such as Reuben Garcia, who has directed Annunciation House for more than forty years. On the back wall of the room in which we met with Reuben is a large crucifix formed of wire boxes attached to each other. In each box that forms the cross is a pair of dusty shoes. They are shoes that were worn by migrants as they made their way through the desert. Staring at the shoes, I could only think of the piles of shoes stacked in the concentration camps, there where the journey ended for so many of our people.

At the Hope Border Institute, encountering more of the righteous, the tzadikim, we were told of how the border has been a “laboratory of injustice,” but for them it is a “landscape of hope.” Our guide into Mexico was a young man named Diego, someone whose life represents the hope waiting to flower from that place. He grew up in Juarez, just over the border from El Paso. As a child, he would go back and forth for school, as so many did, for school, for work, to shop, to visit family. He spoke of his hope for the area, for the “borderlands,” a place that is one community on both sides of the border. He spoke of the gash formed by the wall that cuts through the region, dividing human beings from each other, people who are meant to be as one in the borderlands. It is a beautiful image for the whole world, human communities that transcend the borders between them. That is part of the teaching that rises from the “landscape of hope.”

As we made our way on foot back across the bridge between Juarez and El Paso, we encountered US guards just before reaching the border itself. They are standing illegally on the Mexican side of the border, cynically placed there to prevent migrants from stepping onto US soil, from which they would legally be entitled to ask for asylum. From the bridge we could look down through steel grating and see migrants who had been arrested being herded into a makeshift camp, there beneath the bridge. In that moment I so wished that I had superhero powers, my body and soul aching to swoop down and carry them all to safety. I sang the words of Rebbe Nachman to myself as I cried, kol ha’olam kulo gesher tzar m’od v’ha’ikar lo l’fached k’lal/the whole world is a very narrow bridge and the main thing is not to be afraid at all. I hoped that somehow my singing might help the people below to find courage and not be afraid, even the children.

As we made our way on foot back across the bridge between Juarez and El Paso, we encountered US guards just before reaching the border itself. They are standing illegally on the Mexican side of the border, cynically placed there to prevent migrants from stepping onto US soil, from which they would legally be entitled to ask for asylum. From the bridge we could look down through steel grating and see migrants who had been arrested being herded into a makeshift camp, there beneath the bridge. In that moment I so wished that I had superhero powers, my body and soul aching to swoop down and carry them all to safety. I sang the words of Rebbe Nachman to myself as I cried, kol ha’olam kulo gesher tzar m’od v’ha’ikar lo l’fached k’lal/the whole world is a very narrow bridge and the main thing is not to be afraid at all. I hoped that somehow my singing might help the people below to find courage and not be afraid, even the children.

Standing at the wall that cuts through the heart of the borderlands, I searched for hope in the eyes of the children of Juarez with whom we spoke through the steel slats. With the help of others who could translate for me, I responded to one bright-eyed boy of eleven who asked me my name. When I told him that my name is Victor, he laughed and said, “no, it can’t be, that’s my name.” We laughed and joked for some time. Diego was standing beside me and explained that there is a special relationship between people with the same name. In Spanish, each partner of the same name is called a “tokayo” in relation to the other. I extended my hand through the slats and kept saying to little Victor, “tokayo, tokayo.”

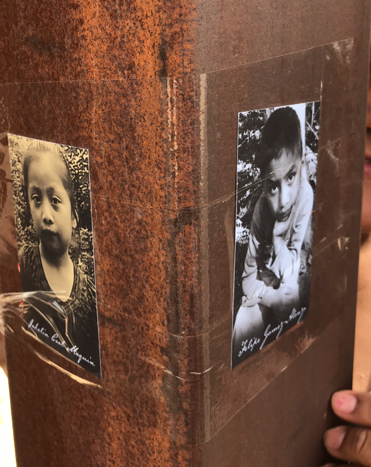

Image courtesy of the author.

Just to the side of where I stood with Victor there were photographs taped to the cold steel, pictures of two other children, Jakelin and Felipe, the two children who died while in detention, their memories blessing the borderlands that it might yet become the landscape of hope it is meant to be. Her fingers gently curled around the steel edges of the slats, touching the photographs, a girl-woman of sixteen spoke with us, telling us of her coming marriage. A child-bride, her words carried wisdom beyond her years, words of lament for the suffering of so many, for those who had died, for those who struggle to find hope as they make their way through the borderlands.

In the shy smile of this girl about to be thrust into womanhood, motherhood undoubtedly not far off, I saw the face of Our Lady of Guadeloupe as depicted in the brilliant colors of a mural on a wall of Casa del Migrante, a shelter that we visited in Juarez. A mother blessing her children, the mural makes clear the extreme dangers of the journey, migrants clinging to the roofs of boxcars as the train approaches a tunnel, darkness enveloping the future, but for the reassuring light of a mother’s smile. We were introduced at the shelter to a woman whose arm was in a cast. She had traveled some two thousand miles on foot from Honduras to Juarez with a broken arm, receiving medical attention only once she arrived in the shelter.

Image courtesy of the author.

In the silent space amid the cracks of my broken heart, I am seeking, searching out the lessons of this journey to the borderlands. It is the silent space from which God calls to us. It is the silent space that we are called to enter in the very middle of the Torah, in the heart of the Torah, the silent space of the borderlands between the beginning and the end, the place where journeys meet as one. In the Torah portion for the week of our journey, Parashat Sh’mini (Lev. 9:1-11:47) we come as migrants to the very middle of the Torah, the silent space that lies between the two words darosh || darash/and Moses diligently searched. So it is for us to search, to seek, to hear God’s call from the very middle of the journey as we seek our way across the narrow bridge, right where the border is. At the very end of the portion, God tells us as we make our way through the desert, ki ani ha’shem ha’ma’aleh etchem me’eretz mitzrayim/for I, God, am the One Who leads you up from out of the land of Egypt. We are one with those who seek the way up from the lands of their suffering, seeking refuge among us. I pray that we shall be as God’s angels, like the tzadikim of the borderlands, helping them to make their way to safety, traversing what might yet be a landscape of hope.

Just before God’s promise to lead us up, at the end of Parashat Sh’mini (Lev. 11:44), we are told, sanctify yourselves and then you will become holy/v’hit’kadishtem vi’h’yi’tem k’doshim. In a very simple comment that goes to the essence of what it means to be holy, the modern Chassidic Rebbe, the Slonimer Rebbe, known as the N’tivot Shalom/Paths of Peace, draws on the classic teaching of the Talmudic sage, Hillel. Offered as a summary statement of all of Torah, Hillel taught: “what is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow” (Tractate Shabbat 31a). We need to imagine ourselves at the border, each as a refugee, asking of how we would wish to be treated.

As Jews, we know what that has to mean. We know the ultimate consequence for us of doors closed to refugees. We see the shoes, the piles of shoes. We know to what ends the “banality of evil” can lead. Upon arriving for the start of this journey to the border, I walked to the El Paso Holocaust Museum and Study Center. Standing in front of the small, closed building, I wanted to affirm at the start of our journey the Torah’s reminder not to oppress the stranger, meant to be felt viscerally by each of us, to be felt in the depths of our soul, the verse that is repeated some thirty-six times, …for you know the soul of the stranger, because you were strangers in the land of Egypt/v’atem y’datem et nefesh ha’ger ki gerim he’yi’tem b’eretz mitz’rayim. What would it mean in the way of knowing the soul of the stranger, and what would be its impact on national policy, if we could see ourselves in every refugee at the southern border, if we could see and affirm our shared humanity?

As we davened Mincha, praying the prayers of afternoon right alongside the border wall, song and prayer wafting through the slats to our young friends, I heard my name called as had never before happened in prayer. My eyes were closed as I prayed the Amidah, touched by fervor, by yearning. In the midst of prayer, I heard my name called by an angelic voice, gentle but insistent, calling over and over again, Veector, Veector, Veector. I began to smile, bursting with emotion, tears of joy and sorrow welling. It was God’s voice calling through little Victor, my tokayo, my friend. So may God’s voice of motherly love be heard in human key, giving succor and hope to all who make their way through the borderlands; giving challenge to all of us who are called to be as the tzadikim, to do the work of Elijah and help turn “a laboratory of injustice into a landscape of hope.”

Ways to help migrants as suggested by T’ruah and HIAS

Supporting Organizations working at the border

Please consider making a donation and encouraging others to do so.

- Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center

- Hope Border Institute

- Annunciation House

- Casa del Migrante en Juarez

Supporting people seeking asylum at the border

Some of the following are specific requests in addition to financial contributions

- Recruiting long-term volunteers (2 week minimum) to work at Annunciation House

- Recruiting lawyers (especially with Spanish language skills) to join a HIAS legal delegation. They can use this form to express interest and HIAS will be in contact if/when we have openings.

- Donating air miles to Miles for Migrants, which has a partnership with HIAS. These will be used for booking flights for asylum seekers.

- Support the emergency shelter run by Jewish Family Service of San Diego – as we discussed on the trip, this is a major response to the border situation by a Jewish organization. Here is the link to donate and the link to their amazon wishlist.

- Here is an amazing list of other opportunities to donate supplies and to volunteer, curated by Love Resists and the Unitarian Church.