For the last hundred years or so, significant portions of the population within so-called liberal democracies in the global north have known comfort, ease, and personal liberties that have been unprecedented since at least the patriarchal turn. It’s not a new phenomenon for some people within a stratified society to enjoy comfort, ease, and freedom. What is new is that it’s been a majority, in at least some of these regions in the world. The unleashing of free and cheap energy following the outsourcing of the worst forms of labor initially to enslaved Africans and colonized countries, and later to large segments of the population everywhere, has made it possible for many of us to be fantastically privileged in terms of what we understand personal freedom to be. We are entirely unprepared for what may come our way. I am writing this in the hopes of supporting us in finding pathways for the really difficult times that some of us believe are coming, possibly inevitably, though I remain humble about what’s to come.

Our privilege is such that I think it’s hard to actually imagine what it’s like to live in an actively repressive regime. We may know in the abstract that many people live in such difficult conditions, and I don’t believe we actually can viscerally feel what it means that so many people wake up in the morning, live their days, raise their children, engage with their communities if they have them, and go back to sleep, and do it all within a deeply authoritarian context, in which what they can do or say is controlled. We also didn’t grow up, most of us, under conditions of war, occupation, or extreme material deprivation. I’ve had the edge of an edge of visceral experience of this, and I still recognize myself, fully, within that layer of privilege that requires immense effort to imagine something else in detail.

When I pause to think about why we’ve had this degree of freedom and ease, I think it’s because the ruling classes have been able to maintain their control of resources without having to control our behavior. This has been especially true following World War II, the immense economic booms that made it possible for accumulation to grow while also redistributing enough of it for others to enjoy. This deal was short lived. Once economic growth couldn’t keep up with the interest rate on loans, the “safety net” welfare programs that were put in place in much of the global north countries started being dismantled and replaced with deregulation and all the other measures of neoliberalism. The impact of this has been captured in a way that most astounded me in an article I’ve referenced before, “The Birth of the New American Aristocracy,” by Matthew Stewart, published in The Atlantic in 2018, innocent of the upcoming pandemic a mere two years later. The gist of it is that while 90 percent of the population in the global north has been losing ground in the last number of decades, and the 0.1 percent has been gaining immense ground, there is one group of people who have maintained their fundamental comfort and freedom, and that is what the author refers to as “the 9.9 percent.” I am clearly one of them given my education and even income. It is a mystery to me how, despite the personal benefits some of us receive from the system as it currently functions, some of us continue to hold on to a vision of an entirely different world and dedicate our lives to moving in that direction.

This is the group of people I engage with most. I believe most of my readers, most of those who come to my free conference calls and to my classes, and most of those who join the Nonviolent Global Liberation (NGL) community and organization are of this group. Not only from the global north. With the infiltration of modern capitalism into most countries of the world, there is now a layer of westernized people in most countries to a greater or lesser degree. I can see how certain values remain local and certain sensibilities, especially ones to do with group orientation, persist. And, still, I see the degree of longing for the ease and comfort of what has been created in the global north in most of those I meet, anywhere on the planet. I do not meet the ones who haven’t and aren’t likely to find a way to cross the barrier of literacy, or the women in large parts of the world who are near banned from public life at all, or the many millions of migrant workers and semi-refugees around the world who are on the go in search of some work to feed themselves and others.

Preparing for what’s coming

I am talking here to myself, and to those of us who see what I see: that there is no path forward that maintains this degree of comfort and isn’t on a collision course with the reality of biological limitations. What is fully unknown to me is how much time is left and what’s going to happen until we either fully collapse or find a way for some or hopefully many of us to walk towards life sufficiently to stop the collapse.

Without knowing, and in full humility, I still have my own sense of what is unfolding. Along with some others I feel aligned with, I am seeing that the turn towards authoritarianism is a direct result of neoliberalism, not some odd deficiency of this or that group of individuals, either those who enforce their power and erode civil liberties, nor those who vote for them. And I anticipate this getting worse and worse over the coming years and decades (if we have decades ahead of us, which remains an open question for me).

As we continue to walk in the direction of impending collapse, it will be harder and harder to maintain the semblance of ease and comfort and freedom that global north countries have known. I anticipate us seeing more and more active repression, because of growing anxiety for more people, including those whose power is sustained by the current systems in place. The recent pandemic has only increased the unimaginable gaps between the extremely few and the many, as billionaires, and our first trillionaire, have increased their share of our collective resources. With more anxiety, I anticipate more attempts to create more control in relation to as many people as possible. I think what we’re seeing now is very small compared to what I anticipate coming in the near future. Within this, I sometimes think of what is happening now as dry run practice training.

One of the turning points for me in thinking about this challenge was reading an article by Margaret Klein Salamon, republished in 2019, called “Leading the Public Into Emergency Mode: Introducing the Climate Emergency Movement.” It was the first time that I understood what it means to live in conditions of chronic emergency. Acute extreme conditions can only go on for so long before they become chronic. What I understood through this article, independently of the implications for climate emergency workers, is something deep and painful about us, as humans: even under extreme conditions, life actually goes on. From when there’s chronic extreme conditions, humans find a way to adapt and find pockets of exiting from the hardship.

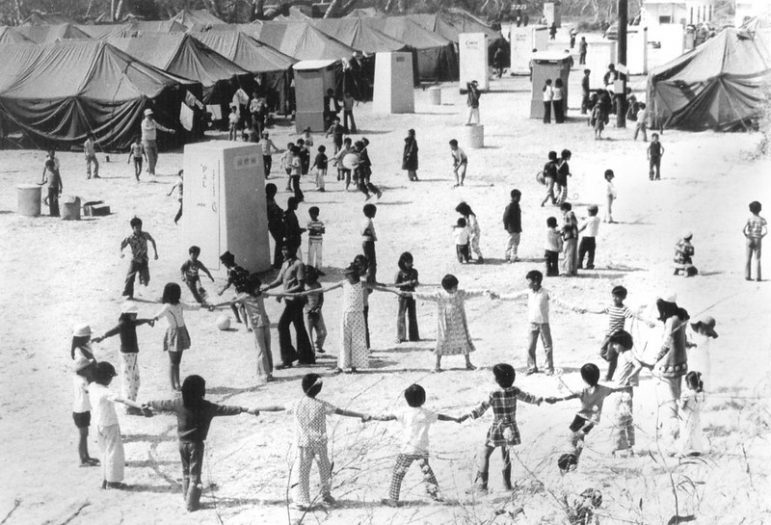

This is true even in refugee camps, and reading the article reminded me of when I first noticed it and didn’t have the framework for making sense of what I was seeing. In 2008, when I was in Ghana, I visited and did some teaching and facilitating in a Liberian refugee camp. The conditions were really, really, really extreme. I don’t have sufficient words for the horrors I saw. Families with multiple children were living in a space that is smaller than one bedroom in the global north, with no electricity and no running water, not even a well. Only water from the UN that was never enough, or black-market water. Still, even under those conditions, I saw people walking around, chatting with each other, laughing, smiling, telling stories, saying hi to each other, enjoying moments of connection. They were still living, and that was in conditions that I would likely not withstand for more than a few days, if that. Simply put: there’s something about us that knows how to adapt to whatever the conditions are.

From this I come back to looking at our preoccupation with civil liberties. Within this context, it’s clear to me that this preoccupation, in itself, is only possible for us because of our privilege. We are simply not prepared for worse than this. And I want us to be ready and to find ways of responding. Not simply so that we, as the individuals that we are, can survive. It’s much larger than this for me. I want us, those who understand what is happening, to act on behalf of all of us. I want us to learn three things that might help us face what may be coming: to find choice within; to honor our limits and know when to choose death; and to walk towards community and life as far as we find pathways to do so.

Finding inner choice

My greatest teacher in this area is Etty Hillesum, who wrote a diary during World War Two. Sections of it were published under the title An Interrupted Life. It’s the diary and letters she wrote between 1941 and 1943, in the height of Nazi rule in the Netherlands, where she lived, between ages 27 and 29. She wrote it all as the world was closing in on her, as a Jew in Amsterdam. It ends when she went to Auschwitz.

There is much that has been striking for me about Etty, and the way I summarize it to myself is that things happened to her in the reverse order from what’s intuitive: the less outside freedom she had, the more inner expansion she stepped into. Her inner life, her capacity for choice, for compassion, for big-picture thinking, became bigger over the course of these writings. The last thing we have of her that she wrote, though she likely continued to write things that didn’t survive, is a note she threw out of the train that took her and other Jews from the transitional camp in Westerbrook to Auschwitz. She dropped a note from the window of the train, and somebody picked it up. The note said: “We left the camp singing.”

Of course, one might easily say, “Well, so what, they still all died.” That, to me, misses the deep point. She found a place to make meaning of her life. We all have this option. We get to choose what kind of a human we are, who we’re going to be, who we’re going to think of, how we’re going to feel, how we’re going to view the people who are oppressing us, how we’re going to view the people who are disagreeing with us, how we’re going to view ourselves, how we’re going to view our impending death. Within that, she found full, total spiritual infinity. She said, towards the end of her stay in the transitional camp, when the reality of transport to Auschwitz was imminent, the following words: “I want to be sent to every one of the camps… I don’t ever want to be what they call safe.” This, to me, is ultimate freedom. And it’s available to us always. No one can take that away from us. It is the essential irreducible aspect of choice and hence our unique humanity, the deepest source of what dignity is for me. I wrote about this, at much greater length, in 2019, in a piece I called “The Powers That No One Can Take Away from Us.”

Knowing when to choose to die

I come from a long, long line of people who died over the years because of their faith. This has been going on since before my ancestors were exiled from the land of Israel. So much so, that it presented a deep theological dilemma that is both simple and horrifying: when faced with the choice to violate any of the practices or observances or to die, what is a Jew expected to do? The rabbis thought about this and came up with a guideline that I have deep, deep appreciation for, even though the specifics are not necessarily a fit for me: it’s better to violate just about everything that comprises a Jewish life – the practices, the observances, and the commandments – than to die. Except for three things. For those three things, if you are asked to violate them, it’s better to choose to die. What this means to me is that there are certain lines that if I cross them, I may as well be dead, because the violation counters my core being. For those observing Jewish law, those three are idolatry, bloodshed, and incest. I can reinscribe these into my own way of being, and reframe them as accepting others’ values, harming life, and not honoring dignity. When I do that, I can find myself within them. And the point is not the specifics. The point, for me, is choosing for ourselves what is truly our value bottom line; the line that if we are asked to cross, we would rather die. I am thinking that choosing it, reflecting on it, and holding fast to it are essential in these times, so that we can do it while we still have sufficient comfort and freedom to reflect deeply. It’s another form of strength that I want us to cultivate, so that we can lose at least some of our fear, because being able to choose despite fear is a hallmark of nonviolence. I think it is time for us to start thinking about what it is that we would rather die than do, and how would that support our discernment about what actions we take now to face what is unfolding in life.

I want to share two examples. One is that, as a Jew who grew up with deep and obsessive awareness of the Holocaust, I have often thought about who would hide me if things came to that. No one thought things would come to that before the Nazis started rounding up Jews all over Europe, so I am not in any way thinking that this couldn’t happen, to us again or to other groups. This is an invitation to think about this as one discernment opportunity. Imagine that someone came to you, a Jew or anyone else who may be persecuted, possibly to death, individually or as part of a group, by the authorities, and asked you to hide them. Would you do this at risk of death to yourself, or would you say no to the person who came? As a Jew, I have only one person in my life that I am 100 percent certain would hide me. Only one. It doesn’t mean that others wouldn’t. It only means that I am not certain, even though some others told me they would. For this person, my dear friend Victor Lee Lewis, I trust what he says completely. I fully trust that he would rather die than give me to the authorities. I want us all to be prepared at that level.

The other example is my questioning of my own capacity to walk towards death in relation to something I feel deeply committed to and can’t know for sure. One particular form of horrific torture that has been common is demanding of one person to torture another or to themselves be harmed and possibly killed. I hope with everything I have that if it came to that, I would say, “Kill me” rather than harm another. In my consciousness, this would be a clear bottom line for me. And, in all humility, I can’t know. None of us can know until the moment comes. All of us can prepare.

Walking towards community and life

It would be unsettling for many, including myself, for me to write a piece about how to respond to things getting worse that doesn’t include any action outside the self. This is what I want to turn to next.

In the last few weeks, I have started thinking of us, globally, as a low-capacity species. I see this happening for at least two reasons. One is that, for thousands of years now in growing parts of the globe, we have been absorbing trauma from the exponentially intensifying patriarchal field within which we live. This is individual and collective trauma, passed on from generation to generation through traumatizing socialization and through deeply constricting institutions. This trauma is what creates the pressing need for accelerated forms of collective liberation.

The second is very related and is more recent. One of the ways we have been weakened and weakened and weakened is by being torn from land and from each other. We have been individualized and made dependent on others we don’t have relationships with for our basic material survival. To be clear, I don’t believe in self-sufficiency. It’s completely fine for me to be dependent on others that I am in community with. That is our human condition. We are creatures that need each other. We can’t survive on our own. In fact, as both David Graeber and Silvia Federici show with great love and potency, being on our own and away from land is what’s made early capitalism possible, in part by making it possible for some of us to be enslaved by others. We are now dependent on people with whom we don’t have relationships. I think of this as a terrible fate, and this is what was done to us. It makes it possible for us both to submit and to oppress. It also makes some of us, those who have been benefiting from capitalism, less able to come together in community. Those of us who haven’t “made it” in the capitalist world, anywhere we are, still know, viscerally, that we need each other. Impoverished communities everywhere, including within the global north, would not make it without each other. And, those of us who are accustomed to relying on money rather than on relationships are far weaker.

We are super-weak in terms of being able to actually come into community and live together again. We are attached to the comfort and freedom that money and some degree of isolation within ourselves or our nuclear families afford us. We are attached, even if we don’t call it that, to having the option of exiting relationships because we can rely on our money to sustain us. Creating no-exit relationships is actively frightening to many. Some years back I remember a heated conversation with two friends who didn’t even recognize “community” as a need, let alone chose it. This is a serious malady of our times.

If we are looking for action, beyond ourselves and our individual choices, I have a sense that it’s time for us to move in the direction of community. Those who read my work regularly will recognize that this is what I have been doing, without even exactly planning it: untethering from the comfort, from the habits that sustain it, from individual existence. It is no accident to me that the initial step towards it was catapulted by relationship with people who are from the working classes, those who haven’t fully lost what community means. My recent newsletters are all about what I, we, are learning about moving towards creating communities with other people that are based on material risk-sharing and not primarily on whether we like each other. We are consciously aware of the reality that we need each other. We are willing to put aside our individual capacity to exit a relationship and rely on money so we can be together to face whatever happens, together.

We are super early in this and have almost nothing to show for it. It’s been hard and it’s been magical, both. And we see ourselves not as an experiment in collective exiting from the mainstream. Quite the opposite, in fact. We see ourselves as experimenting and learning on behalf of humanity, consciously committing to sharing all we learn with others, inviting others to do their own experiments, offering support and coaching, and longing to link arms with other communities similarly committed. We don’t yet have a place on earth we call home. At least some of us are hoping to be there within a year. Eventually, if enough of us do this and share the learning, we can inspire many more to experiment, and we can then begin to connect dots between such communities. Then we can maybe form an alternative infrastructure, if we are not actively undermined by the existing ruling classes, which has happened many times before to many others in the hundreds of years since capitalism started fighting its way to being the dominant social order.

Having studied history at least to some degree, I don’t believe we currently have the power to take on the large systems in the world and change them. Unless really many, many millions of us manage to come together with a strong vision, I don’t know how we are going to unsettle the systems that exist. Although I deeply believe in collective action, I don’t see a vision compelling enough, bonds compelling enough, and strong enough capacity to function outside of patriarchal scripts to be able to create and sustain the possibility of catapulting people en masse. I may be mistaken. I’d like to be mistaken. And when I look at the historical record, what I see is that we have been unsuccessful in doing that for the entire time that patriarchy has existed. If I look at the last five-six thousand years, it has been, almost linearly, that fewer people have more access to more resources, and more people have less and less access to resources. The distribution of resources has become progressively more skewed. From Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch I learned, among many other reasons, about the last major time in which people actively stood up, from within communities and on land, and for many decades, to the emerging new social order. They failed, even when still connected to land and each other. We who are less so are unlikely to succeed. And I am not surprised that major movements that have managed to have some partial transformative results have been movements of the impoverished and the oppressed – in India, in parts of Africa, the marginalized in the US, the Kurds in Rojava, those within overtly authoritarian regimes; not in the rich countries of the global north. There has been simply too much legitimacy for those regimes for enough people to come together and rise up.

This is why I am thinking that the small-scale experiments like the ones I am involved with are a viable, even if modest option, for those of us who are not part of existing communities and who want to forge a pathway. I want all of us of us who see those possibilities to start coming together with others as much as we know how. I want us to find our collective visions and from within them walk towards the discomfort of losing our individual comfort and hyper-autonomy, so we can find choice within togetherness, as our evolutionary makeup designed us for.

We know, there is enough evidence, that collaborative, self-governing, small-scale communities and organizations are often amazingly resilient and solid. The stories are breathtaking, and mostly hidden. The question, for me, is no longer about whether small-scale experiments can work. It’s only about how we can gather sufficient momentum to transcend the logic of patriarchy and capitalism on a larger scale than a small community, by connecting dots. It’s not given to us to know whether we will succeed. It is given to us to participate.

PHOTO CREDIT

White man facing cliff’s edge – Photo by S Migaj on Unsplash

No more house – Photo by NOAA on Unsplash

Ring of kids at Camp Pendleton – Photo from manhhai on Flickr

Etty Hillesum (glaspositief), circa 1939 – Public domain thanks to Joods Historich Museum

Three at the cliff – Photo by Jonas Wurster on Unsplash

Fruit stand – Photo by Jim George on Flickr