As a child, I was always struck, when reading 19th century novels, by figures about annual amounts of money given to people. I couldn’t figure out, even taking into account insane inflation rates, how it would have been possible for anyone to subsist on those amounts. In preparing to write this piece, I just discovered that, in the US, the average wage in 1790 was $65. In today’s numbers, this would be a whopping $1,300 per year, or about $3.50 per day. What’s going on here? How did people then survive? And, more acutely, how is it that people manage to survive on 25 cents a day now, as is the minimum wage today in Sierra Leone?

Then as now, the answer is that in those days and in many places around the world still, the majority of people either live on the land or are, at least, interwoven with communities that are on the land. Under such conditions, much of what people require for their sustenance is produced outside the market, and large numbers of people only work to supplement what was taken away from them through land appropriation and other enclosures of what previously may have not been monetized at all. Even in the most industrialized and urbanized societies, still the invisible gifting goes on, more often than not by women: the work of care, what Marx called “reproduction.”

Despite all of this, capitalism has won a major battle in successfully reducing work to jobs. Even those who are championing equality, justice, and visions of a better future are calling for “Jobs for All” or “Fight for 15.” I grieve this because to the extent that work is a process of attending to three basic needs – sustenance, dignity, and meaning – the overwhelming majority of the world’s population is doing work in the form of jobs that are insufficient for sustenance, assault workers’ dignity, and lack meaning. Even when the pay is sufficient, jobs are still lacking in dignity and meaning. This is documented, with painful example after painful example, in David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs, which I reviewed here. I grieve because I hear almost nowhere a call for a fundamental restructuring of our entire approach to work.

Despite all of this, capitalism has won a major battle in successfully reducing work to jobs. Even those who are championing equality, justice, and visions of a better future are calling for “Jobs for All” or “Fight for 15.” I grieve this because to the extent that work is a process of attending to three basic needs – sustenance, dignity, and meaning – the overwhelming majority of the world’s population is doing work in the form of jobs that are insufficient for sustenance, assault workers’ dignity, and lack meaning. Even when the pay is sufficient, jobs are still lacking in dignity and meaning. This is documented, with painful example after painful example, in David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs, which I reviewed here. I grieve because I hear almost nowhere a call for a fundamental restructuring of our entire approach to work.

Unpacking “Essential Workers”

Before the pandemic, we all knew already that however much we have mechanized, automated, and virtualized our world, there would always be a need for human hands touching other material objects and other human bodies in order for human life to continue. And yet those of us doing other types of work almost never talked about it. I am guessing at least two reasons for this silence. One is likely that we are – or can be – ignorant of this reality, the way, almost always, that privilege is set up in a way that makes it so easy for it to be invisible to those who have it. Talking about it would expose the privilege, and it’s morally challenging to recognize that our comfort is at cost to others who toil to satisfy our needs, even if indirectly so. The other, perhaps, is that for many of us our privilege gives us, in addition, an illusion of self-sufficiency; a kind of safety that comes from depending on no one. Whereas the reality is that our lives and our comfort lean on so many hands doing so many things we know not how to do.

For myself, any time I saw announcements about this or that program that would promise some path to finding our passion or purpose and then converting it to some way to work and make a living, I would think, ruefully, about what I called “the garbage problem”: someone still needs to collect the garbage; someone still will do work, day in and day out, that isn’t their “passion” or “purpose.” Until and unless whoever creates this program attends to the garbage problem, there will continue to be people who do work that isn’t fulfilling, that is usually low paid, and that puts them at risk, now heightened during the pandemic.

This is where the Coronavirus crisis is opening up yet another conversation that was previously not possible: a potential deep dive into the nature of work and, through that, how we care for all of us.

This pandemic has divided us into three groups: those who either don’t need to work or can work from home; those who must work at greater risk and exposure to themselves because their work is considered “essential”; and those whose work isn’t considered “essential” and can’t be done from home, many of whom have lost their jobs to staggering rates of unemployment.

Clapping hands at 6pm across balconies in Italy for health workers, and then elsewhere notwithstanding, being categorized as an essential worker brings no comfort, joy, protection, or even care to those doing that work, however much the work itself does for some. Within days of the lockdown beginning where I am oddly situated in Glasgow, I encountered a garbage collector on my way back from a walk. In my attempt to convey to him my own individual and inconsequential-yet-human sorrow about the predicament that he and his fellow workers were in, it took three attempts for him to actually receive in full my message, at which point he lit up and became talkative and animated. My sense in the moment was that the separation between classes is almost impenetrable, and his organism no longer expects anyone to care, so my expression of simple human care didn’t have anywhere to register. I left that scene brokenhearted. Even a cursory look at what essential workers are saying shows that there is no sense of respect or dignity that comes from being named this. An article in “The Conversation” makes it abundantly clear that what is “essential” is the work, the service rendered or product made; not the worker, the person whose labor makes that service or product possible. Otherwise, efforts would go into protecting them rather than exposing them to increased risk, as has been the case. Given that so many of those doing such jobs are Black and brown people or migrant workers, mostly women, I see an added dimension of race and gender overlaid on the already brutal class gap.

Clapping hands at 6pm across balconies in Italy for health workers, and then elsewhere notwithstanding, being categorized as an essential worker brings no comfort, joy, protection, or even care to those doing that work, however much the work itself does for some. Within days of the lockdown beginning where I am oddly situated in Glasgow, I encountered a garbage collector on my way back from a walk. In my attempt to convey to him my own individual and inconsequential-yet-human sorrow about the predicament that he and his fellow workers were in, it took three attempts for him to actually receive in full my message, at which point he lit up and became talkative and animated. My sense in the moment was that the separation between classes is almost impenetrable, and his organism no longer expects anyone to care, so my expression of simple human care didn’t have anywhere to register. I left that scene brokenhearted. Even a cursory look at what essential workers are saying shows that there is no sense of respect or dignity that comes from being named this. An article in “The Conversation” makes it abundantly clear that what is “essential” is the work, the service rendered or product made; not the worker, the person whose labor makes that service or product possible. Otherwise, efforts would go into protecting them rather than exposing them to increased risk, as has been the case. Given that so many of those doing such jobs are Black and brown people or migrant workers, mostly women, I see an added dimension of race and gender overlaid on the already brutal class gap.

Overall, with very few notable exceptions (such as for medical doctors), the more essential and the more care-based someone’s work is, the less well-paid they are, and, often, the less dignity exists in their working conditions. The reasons for that are complex, and quite beyond the scope of a short piece. Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs digs deeply into these painful topics and I urge anyone interested to read it.

If that were not enough to provoke wonder about this category of “essential worker,” that same article, and what I had read elsewhere before, also makes the point that it’s not entirely clear what is essential for attending to actual needs, and what is essential for keeping the economy going, and the two are used interchangeably in a way that blurs the distinction.

Ultimately, based on David Graeber’s research in Bullshit Jobs, and thinking about these questions deeply while writing Reweaving Our Human Fabric, I am prepared to conclude, without knowing where to look for further evidence, that a staggering amount of current jobs are either bullshit jobs or shit jobs as Graeber defines these categories. In either case, they are jobs that are fundamentally there to sustain the current system, such as through gatekeeping (think insurance company clerks, toll booth operators, licensing agencies, and then you might recognize just how far this can go), through serving those with more resources (many jobs in the service industry fall in this category), or through protecting the powerful (as is the case with armies, police, and others).

Again, as with just about everything that I am speaking of in this series about the Coronavirus situation, there is nothing new about this state of affairs. The only thing that’s new is that the veil put over these questions which makes only few of us talk about them has now been lifted. The reality that essential work is done by people who are not cared about, and that enormous amounts of inessential work are continuing as if they were essential, is now in plain sight. Here are just two quotes from an article in the “Vox” based on interviews, many of them anonymous, with essential workers around the US. The first is from the author, Emily Stewart: “The coronavirus crisis has exposed many ugly truths about America, how underrecognized and underappreciated essential workers are, not just during a pandemic but always.” The second is from a worker at Walgreens, a large retail chain in the US: “They really don’t care about us, they just care about having someone there to help them make money.”

A Different World Is Possible

As I was writing the twelve stories that make up the fictional account of a future world included in my book, it slowly dawned on me that each of these stories was in some ways a response to some implicit or explicit skeptical questioning I’d either heard or imagined. As it relates to work, the stories deal with real or imagined scarcity; with the problem of freeloading; with the very intense reality that not everyone can contribute in their preferred way; and with a host of other smaller questions. While writing them, my experience was more one of visiting, rather than imagining, that world. I was writing from within that future reality rather than from here, looking at it. Each time I finished a story, I had a similar feeling of a shocking thud when I landed back in this reality seeing it unchanged by what I had just discovered.

Unsurprisingly, one of the challenges I took on to “solve” in a story was exactly what I earlier referred to as the “garbage problem:” the utter clarity that there will never be enough people who would have active willingness to collect garbage day in and day out as their main thing in life. Why would anyone do it if it wasn’t because they couldn’t see any other way to feed themselves and their loved ones? This, in a nutshell, is one of the core fundamental acts of violence that capitalism brings to us: forcing most of us to do things we wouldn’t otherwise ever agree to do. In the world I visited, such work is rotated. I know that I would be totally willing to collect the garbage from time to time, and I have ample confidence that so would enough people to care for that task – and any others that have that same characteristic – from willingness alone. And there is no need, either, for everyone to rotate; only those of us who are willing. This is the deepest essence of what could be different in that world in regards to work: only that for which there is true willingness is done. There is no coercion in that world, not direct and not indirect through so-called incentives. Only willingness.

Unsurprisingly, one of the challenges I took on to “solve” in a story was exactly what I earlier referred to as the “garbage problem:” the utter clarity that there will never be enough people who would have active willingness to collect garbage day in and day out as their main thing in life. Why would anyone do it if it wasn’t because they couldn’t see any other way to feed themselves and their loved ones? This, in a nutshell, is one of the core fundamental acts of violence that capitalism brings to us: forcing most of us to do things we wouldn’t otherwise ever agree to do. In the world I visited, such work is rotated. I know that I would be totally willing to collect the garbage from time to time, and I have ample confidence that so would enough people to care for that task – and any others that have that same characteristic – from willingness alone. And there is no need, either, for everyone to rotate; only those of us who are willing. This is the deepest essence of what could be different in that world in regards to work: only that for which there is true willingness is done. There is no coercion in that world, not direct and not indirect through so-called incentives. Only willingness.

The only way for that level of freedom to exist is to have a matching level of togetherness. Without it, we continue to be each on our own, fending for ourselves and our close loved ones, protecting ourselves from, and competing with, everyone else. With it, we rest in collective care for everyone’s needs. This is what we can now see the bare outlines of during the pandemic. This is what our souls know now, more than before, is possible.

This is the world of the gift economy writ large, about which I have written many times. Gift economies are simply economies based on needs, and on uncoupling giving from receiving, so that needs are attended to because they exist, not because we deserve to have them met (as is the case in both capitalist and socialist social orders). Small scale gift economies have existed and continue to exist, both visible and invisible. Every one of us was a one-person experience in gift economy in what we received from adults around us when fully dependent on them. Our souls never forget.

Imagining a Pathway Forward

Large scale economies based on needs have failed to engender actual freedom even while speaking of a better future. My own sense of why is that millennia of mistrust of self, of our needs, of others, of life, exacerbated by capitalism, have led the architects of socialist experiments, both in the immense socialist states and in the Kibbutz movement, to require an external authority to determine both needs and ability. That meant central planning. That meant coercion.

When I read the book Fan Shen, detailing the transition from feudalism to semi-imposed collectivism in one Chinese town during their revolution in 1948-1949, I understood the magnitude of the challenge: what it would have taken to transform, on a large scale, hundreds of millions of people from domination and subservience to collaboration is a task I don’t at present know how to address.

Whatever the reasons, the principle of willingness has never been adopted on any significant scale. This is a deep and sobering reality I don’t want to dismiss or ignore. I am quoting from a piece in a forthcoming anthology called “Attending to Needs without Coercion”:

This reality has left me with enormous questions: what will it take to envision, and then to create, a future “Beloved Community” in which coercion is truly absent? How far can the principles of maternal giving be extended into actual organizing principles of an entire society? And how will we ever reclaim the necessary trust in ourselves, each other, and life after millennia of patriarchy?

I don’t know the answer to any of these questions, nor do I believe that anyone else does. What I do know is that the more we envision boldly; the more we challenge within ourselves the deeper assumptions of scarcity, separation, and powerlessness that patriarchy rests on and capitalism intensifies; and the more we experiment, individually and collectively, with living as if the world we envision were already here, the more likely we are to answer these questions and create at least small pockets of a livable future.

Beyond whatever we can each do in creating pockets of the future, a little virus is creating conditions that open up possibilities previously unheard of at the very same time that it is shattering so many lives. I mentioned already in part two of this series that we are seeing two forms of direct response to needs arising: one governmental, and one community-based. Until and unless we completely revamp the capitalist social order, these are our only options, because, as I said in that piece, markets are incapable of responding directly to needs. Here are the immediate scenarios I see as entirely plausible. The first two either have significant research to back them up, or already exist in partial form, or both. The third is something we all can begin to experiment with.

Universal Basic Income (UBI)

Many countries in the world are now offering one form or another of direct cash transfers to their citizens. Those include a one-time fixed amount to everyone; ongoing cash payments, even beyond the pandemic, to low-income citizens; and various configurations that support people who have lost their jobs, or even those who haven’t. A sample of such measures in various countries can be found in this “Business Insider” article from early May.

For the most part, these measures don’t qualify as universal basic income (UBI), because they tend to be conditional and/or given only to part of the population. There is only one country in the world where nationwide ongoing UBI exists: Iran. However, there have been and continue to be many experiments in UBI, as well as some places where more local UBI is an ongoing part of the economy, many of them surveyed in a “Vox” article.

For the most part, these measures don’t qualify as universal basic income (UBI), because they tend to be conditional and/or given only to part of the population. There is only one country in the world where nationwide ongoing UBI exists: Iran. However, there have been and continue to be many experiments in UBI, as well as some places where more local UBI is an ongoing part of the economy, many of them surveyed in a “Vox” article.

I find UBI fascinating, in part, because supporters of it range from economist Milton Friedman who was advisor to Reagan when neoliberalism was first established in the US all the way to David Graeber, anarchist anthropologist and economics historian. Anything that such a wide range of people believe in immediately piques my interest. In addition, as the article I just referred to indicates, as well as other reading I have done over the last couple of years since UBI first came to my attention, the concerns about UBI – that it will disincentivize work and reduce productivity – have been mostly disproven. UBI, where it has been experimented with, results in greater spending in areas of food, health, and education, and contributes to well being and greater trust. UBI is Graeber’s suggestion for a way out of the trap of “bullshit jobs.” Certainly, when some basic benefit exists, the fear of losing a job that keeps so many people willing to absorb humiliating work conditions and meaningless jobs drops, leading, possibly, to increased freedom. Longer term consequences, I believe, are too difficult to anticipate.

As intriguing as UBI is, and as much as I am aware of how much benefit it has brought to people, I have two big concerns about it. One is that UBI operates fully within the market economy, and is only offering people a better position from within which to compete in the market. This is no small gain for those who are impoverished by the current system, and I wholly support that. I also am fully on board with Graeber’s point that the universality of UBI is what makes it possible to administer with almost no added bureaucracy, the primary reason leading him to support UBI measures. I am just unsure that UBI is the best we can do.

My second concern is that UBI schemes mean that everyone receives the same amount of money, regardless of need. My own wish is that resources flow to need, not to an abstract principle of equality. I am well aware that anything that is means-tested is entirely fraught with difficulties, and that is emphatically not what I am proposing. I am simply noting that UBI schemes sidestep these limitations rather than addressing them. Still, given the wide support that UBI has, and the fact that it makes a more significant dent the more impoverished a person is who receives the money, I stand behind such initiatives despite my concerns.

Universal Basic Services (UBS)

A related though very different type of program has started gathering attention in the last while under the heading of Universal Basic Services (UBS). UBS schemes build on and expand from already existing programs in many parts of the world which offer free services to people in areas such as healthcare and education, to include additional areas such as housing, transportation, childcare, and a few others. The particular package is not uniformly decided, nor is there clear agreement among proponents about how services would be offered and paid for, nor, ultimately, whether they would truly be free or whether they would be at least in part means tested.

UBS is a much younger area of social thought, and thus more questions remain open within this scheme than with UBI. I find it intuitively appealing because of the fact that under this plan people would receive a service because they need it, which is close to the image of the world I have been envisioning for decades, in which resources flow from where they exist to where they are needed. I also like these plans because they are not dependent on having money at hand, again making them close to the world I envision, a world in which there is no money and no exchange. In principle, UBS schemes appear much more like a narrow version of a gift economy than anything else. In addition, with universal access to schooling already a reality in a large number of countries (a reality I am at odds with in that I am not in favor of sending children to school, and that is entirely a different matter), with universal access to health care available in at least some countries, and with other services available to people in fewer locations (such as free access to transportation in some locales), there is something here to build on – and still the obstacles are immense to make it a viable reality.

One core concern is whether such programs can viably be administered without means testing, which everyone acknowledges as highly problematic. Making services truly universal and thus avoiding complex, often demeaning selection plans which are regularly ineffective at finding all the qualified people raises the second concern, which is that many believe these programs would become prohibitively expensive. A third concern is about who administers the programs, in that leaving it all in the hands of government maintains some form of centralized control which isn’t conducive to localized economies, which I believe are absolutely key to a future that works for all of life. I still continue to believe that such programs are more aligned with the future I want to see than UBI schemes are, and that as proponents continue to engage with the critique more nuanced and creative solutions will arise that localize services, put them in the hands of communities to administer and care for, and embrace growing trust that few enough people would abuse such services that there will be sufficient willingness to let go of any means testing and to allow all who request the service in question to receive it. Until then, it may well be that UBI schemes will be necessary for now in order to move things forward in terms of creating more freedom for people.

Relocalizing: Shared-Risk Communities and the Commons

Both UBI and UBS mostly attend directly only to material sustenance, and, with that, indirectly to dignity. Neither of them have any direct impact on the quality of work itself. Some proponents of UBI in particular claim that if the amount given unconditionally to all is high enough, this would shift the dynamics of supply and demand in the labor market, and may eliminate some of the worst forms of job exploitation and degrading conditions that exist. Whether or not such changes would indeed happen, it’s clear to me that neither scheme provides any kind of fundamental restructuring of people’s relationship to what Marx called “means of production” and their capacity to care for themselves, their loved ones, their communities, and life as a whole beyond and outside the sphere of influence of the market. My own belief remains that finding pathways for doing just that is inescapably necessary if we are going to transcend the disastrous mechanisms of spiraling production and consumption that are so potently supercharged that even when they have slowed down so considerably given the pandemic, they haven’t stopped and the pressure to restart them is immense. So immense that, in the US reopening parts of the economy has started despite clear information that it would exacerbate the spread of the disease. (And I am saying this without at all implying that lockdown measures are the best or only way to attend to the pandemic. I am very uncertain about any of it given my small exploration of different approaches around the world.)

Still without knowing where to begin such a transformation given the very limited support for such shifts that exist, I want to conclude this piece with an exploration of what can begin as tiny experiments within communities and yet, if successful, can build up to challenge the hegemony of patriarchal and capitalist systems while creating a viable alternative way of organizing work and the provision of resources for our needs.

What I describe here in very cursory terms begins with an insight I picked up from Charles Eisenstein’s Sacred Economics, where I fully took in for the first time that what we now call communities mostly aren’t that, because we have divorced the provision of material needs from the relationships we have with those with whom we are in physical or relational proximity. This makes communities weaker, since we no longer have practical bonds tying us together with those around us, and at the same time makes us more dependent for getting our needs met on large, faraway institutions and people we don’t know. It became clear, then, that restoring community means bringing back together the ties based on shared interest, personal affinity, or physical proximity with the material dependence on each other. This may be intensely frightening to many in the global north, and is entirely familiar to the impoverished everywhere, and to most in the global south in particular.

This insight came together with my readings and conversations about the commons. I now understand the destruction of the commons, around the globe, as a tragedy beyond any words I could bring to it. My gut intuition, unprovable from my vantage point, is that living within fully functional commons provided something literally to stand on to resist the entry of patriarchal conditioning into us; a place of togetherness and flow that persisted for a long time however small, local, and apparently flimsy each commons community might have been. To this day, still, in Africa, even as the destruction of the commons is unfolding in intensive, brutal ways, they continue to serve as that foundation. For many who live urban lives, there is still some village, some community tied to land and to each other in bonds of practical resilience, that they can lean on. There is nothing backwards about the African staunch and persistent resistance to entering the capitalist world market, as much of mainstream media would present it. Rather, I see this as a last call for humanity to halt, to stop, to wake up. This call is coming to all of us from the continent whence we all came, initially, in the name of togetherness, in the name of faith in life. The commons has been a robust and creative way for humans to be in reverent relationship with life and to maintain togetherness with each other. The commons is a way of sharing risk that all our ancestors lived in and that many of our fellow humans now are struggling, in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, to sustain. I want to listen and learn. I want to speak of what I learn. I believe we can regenerate the commons, in places rural and urban alike. It may be too late. We don’t know.

This insight came together with my readings and conversations about the commons. I now understand the destruction of the commons, around the globe, as a tragedy beyond any words I could bring to it. My gut intuition, unprovable from my vantage point, is that living within fully functional commons provided something literally to stand on to resist the entry of patriarchal conditioning into us; a place of togetherness and flow that persisted for a long time however small, local, and apparently flimsy each commons community might have been. To this day, still, in Africa, even as the destruction of the commons is unfolding in intensive, brutal ways, they continue to serve as that foundation. For many who live urban lives, there is still some village, some community tied to land and to each other in bonds of practical resilience, that they can lean on. There is nothing backwards about the African staunch and persistent resistance to entering the capitalist world market, as much of mainstream media would present it. Rather, I see this as a last call for humanity to halt, to stop, to wake up. This call is coming to all of us from the continent whence we all came, initially, in the name of togetherness, in the name of faith in life. The commons has been a robust and creative way for humans to be in reverent relationship with life and to maintain togetherness with each other. The commons is a way of sharing risk that all our ancestors lived in and that many of our fellow humans now are struggling, in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, to sustain. I want to listen and learn. I want to speak of what I learn. I believe we can regenerate the commons, in places rural and urban alike. It may be too late. We don’t know.

There are barely any blueprints for those of us in the global north. And it still remains the case that, for the most part, we have lost our capacity to provide for and with each other on the material plane. It’s hard to imagine how we can jump start that depth of interdependence again. And there are still steps that some of us are beginning to discern in the chaotic mess that our traumatized relational landscapes have become. These are but faint contours of a future rooted in a past we have forgotten without forgetting. The most basic step I know is to move always towards rather than away from. There is plenty of heartache on this path, and glorious moments of clarity, joy, and togetherness beyond what we knew before. Until we relocalize food, shelter, and clothing, our shared risk will be more dependent on stubborn will than necessity, and hence less solid, because we still can walk away from any experiment in pooling resources and sharing them based on willingness and need. Much of my attention, these days, is drawn to the creation of such communities, both virtually and on land. In both cases what needs doing and what sustains are to be shared based on need and willingness. The learning is slow. The Nonviolent Global Liberation community is one imperfect such experiment. Our three-person month in the desert about which I wrote here is another. Two of us are now vagabonding together, determined to persist in moving towards and learning. There is much surrender to our smallness and to mystery. One small step at a time. Each of us where we are. Towards, not away from. No act of separation justified, only mourned, always temporary, until we find capacity to come back to togetherness. So long as I can breathe and write, I vow to share what learning I find along the way.

Photo credits

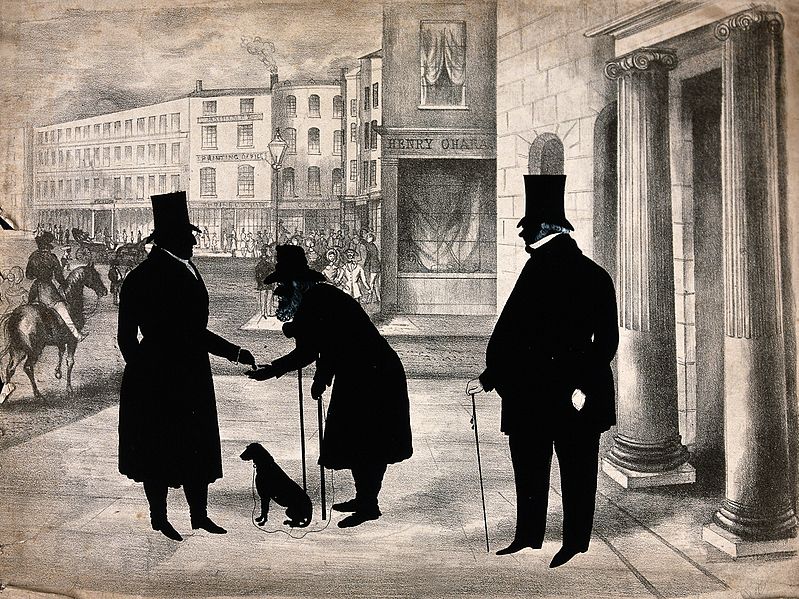

Featured image, lithograph, Man in coat hands money to beggar, free to use, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_man_in_a_coat_and_top_hat_hands_money_to_an_old_beggar_wit_Wellcome_V0039963.jpg

War on the big pink bullshit, by Dunk, free to use, Flikr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dullhunk/2346562184

Essential worker, by Paul Sableman, free to use, Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Essential_Worker_(49911544771).jpg

Full trash can, free to use, Libreshot https://libreshot.com/full-trash-can/

Monopoly board game by William Warby, free to use, Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/wwarby/11513424364

Cauliflowers in Egypt by Ed Yourdon, free to use, Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Wiki_Loves_Africa_2014#/media/File:2008_Veg_Egypt_3140277021.jpg