I began writing about love in an empty hotel lobby cafe after tripping on my way inside and falling on my knees – perhaps a brief, accidental prayer. I tapped onto a screen some broken sentences, while paramilitary and hate groups were gathering in Washington: preparation for the murderous assault on the Capitol was happening as dusk fell in Melbourne, on January 5th, 2021.

Rising to leave a couple of hours later, my second coffee finished, twilight had fallen: dusk, dreaming its shadowy dreams, embracing both the gum trees and the introduced Europeans oaks.

I was frightened that night, without knowing why: a familiar fear to me now, bone-marrow deep. Wordless, vertiginous.

Tiny, mysterious shells or labyrinths – the semi-circular canals – curve within our inner ears. Almost filled with fluid, they sense the movements of our heads: they tell us when we lose or find our balance, and are connected to our cochleae, with which we hear. Vibrations of air are perceived as sounds. Surely the cochleae must also feel vibrations in the ether: from across the world, from across time, from below our feet, and from miles beneath the earth. For we know, in a distant and mysterious way, the rumbles of mining – metals, coal, and iron ore that we should not be taking from the earth anymore.

Breathe, I said to myself.

Breathe, don’t panic. You’re giddy, don’t fall over again, it’s dark now.

Round…. like a circle in a spiral, like a wheel within a wheel,

Never ending or beginning on an ever-spinning reel

The Windmills of Your Mind – Theme song from the 1968 film, The Thomas Crown Affair.

The

My parents played a love song when I was a child. It still plays within me, The Windmills of Your Mind, the whirling ‘long baroque melody’ of Michael Legrand, over and over.

I play it as I drive home: dark now. Noel Harrison (1968) sings it for me. My playlist knows I need comfort, and I sing also with Harrison – although I never get the words right, and although it’s not at all a happy song: memories and are love lost, compass points go missing. But it revolves me, the melody turns me around, and reminds me of love.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

Love is many-meaning-ed, and there are infinite splendours and pains in Love, every kind. We think of romantic love at first, of course – its wild, utter insistence, its longing and terror, its gorgeousness. It pulls us from the too-cool twilight that is our inner solitude towards the warmth of a heart that resonates, lips threaded with scarlet, moments of our souls being recognized. Pomegranates, figs, fragrant oils, The Song of Songs. We are moved – not geographically (although I have moved to other cities for love) – but in relation to our own positions about ourselves. I see possibilities in you that you cannot see without my eyes. And both of us beneath the canopy of love, you do the same for me.

There is a midrash (teaching) about a dark time in Hebraic history. Pharoah had decreed that all male Hebrew children born – children of slaves – would be killed. The men’s spirits were crushed and all despaired. They left for their work in the fields or the quarries without returning at night to be with their wives. In defiant response, the women organized: they pummelled and shone their cooking pots into mirrors and visited their husbands with food. They pointed at the men’s reflections in the mirrors, made them gaze at themselves, and told them: “See how beautiful you are, my husband! How beautiful!” The men began to laugh – and returned.

How beautiful we all are. All human beings.

Romantic love gets a bad rap these days: we’re told it is type of madness, an addiction, a burst of dopamine and oxytocin: destined to last a year or two at most. I am deeply suspicious of this story. What’s wrong with love lasting forever?

Neo-liberalism, capitalism-on-steroids, is one thing getting in the way of people loving each other all their lives. “I’d be better off with someone else,” we say: or “another person would be a better deal for me,” – a marketplace of bodies and beings. And the world of work makes us exhausted by the end of the day, with little of us left to be loving to our partners when we get home at night. Or, working from home, we’re exhausted already.

One of my favourite books, Can Love Last? by psychoanalyst Stephen A. Mitchell, poses the question of whether we unconsciously domesticate love against its will. Perhaps we make love cozy and even boring, Mitchell suggests, so that the demands of romantic love (its creativity, intensity, and its insistence that we see each other clearly) cease to ask so much of us.

Following Mitchell – he died at the height of his creative powers, at fifty-three years old, leaving Relational Psychoanalysis (a “turn” in theory and practice that he largely created) bereft without him – I say that the domestication and farming of animals doesn’t seem to have done them much good overall, and love’s domestication should be with similar ambivalence and caution. Is being ‘in love’ a state of creative wildness, a brumby galloping through wind-tossed trees, plunging through the hills and valleys of our moods and personalities, disappearing for weeks or more – but always returning?

Of course, we’re frightened of being trampled and left in the dust. Love requires so much courage.

Romantic love is a template, a study, for all other types of love. Because Love is impossible to speak of as a whole, I must write in fragments, in pieces of mosaic. Yesterday, digging in my garden, I tipped over a thick plaster tile, one side painted, gilded, lovely, with images of strange birds, flowers, vines. It smashed on the tiles of the patio: small and large pieces, but probably not too many to glue together, even though I was careless with the smallest. Writing and talking about Love becomes like that. Fragments, circles, spirals. We know and feel love to be One Thing (although not a ‘thing’,) but inevitably, a straight line of words kaleidoscopes it, except in the greatest poems – which still mostly shatter it. Language cannot capture the ineffable, of course: the teacher points to the moon, but the pointing finger is not what the disciple should look at. So, I watch my cat, Clementine, as she rubs her chin along the side of my laptop: is she pointing with her nose to the empty page? Perhaps she wants her lunch. Her carnal self is a teacher also, reminding me of my body, my fingers on the keyboard, this hard wooden chair, the delicious croissant dipped in coffee I’ve just eaten.

Outside, I know the skyscrapers and city offices are silent, Covid-quieted. And yet still they build apartments, more and more, although what they build remains indifferent, much less useful than Palaeolithic standing stones which at least had probable astronomical purpose. The tall buildings are stony in their unassailable heights and their logic that it has to be like this, and their statement that this what we are: competitors in a Hobbesian world where without government life would be nasty, brutal, and short. But Western governments tend to favour corporations (ironically named, since corporations are not corporeal – yet corporations are treated like persons in American law, and increasingly in ours) rather than supporting people in caring for each other or investing in Love.

Over twenty years ago I returned from psychiatry training in the US, and scribbled this in a notebook:

“This is what I learnt in seven years – a truth so simple we all know it. It is written on our flesh and engraved so deeply on our hearts that even after years of ‘education’, of being conditioned into believing the madness that we are all separate and alone, and after almost endless enforced submission to the idols of money and ‘success’, we recognize it almost instantly, remembering it as if it had never been forgotten (sometimes it takes mudslides, storms, bushfires, raging tides that sweep our homes away, but then we remember) — Our fundamental need and purpose is to give and receive love. Our submission to ‘economic rationalism’ is not rational, nor separate from mental illness. A culture that values profit above all cannot even grant coherent meaning to ‘us-together’ and our increasingly desperate reach for meaning, love, and purposeful work.”

In Love – romantic or otherwise – we recognize another person as a being just like ourselves. You are a being, in the same way, I am a being – creaturely, with salty tears, salty blood: and as I do, you long for love, peace, and happiness. And yet you are also different, preciously different, and ultimately unknowable.

(Are there individuals? Can we exist without each other? Winnicott said “There is no such thing as a mother and a baby.”[1])

The opposite of every great truth is another great truth, including this one. So, paradoxes abound – not to confound us, but to push for impossible resolution or evolution, and illuminate something that is darkly hidden behind the many swirling veils of ideology, the smokescreens of coal stations, the many machineries of extreme capitalism.

We, the 99%, are free to sell our labour as long as we sell it for nothing much.

We are free to imagine the scenes in Netflix series, series seven, episode five, but usually unfree to imagine a world of Love and equality. Love is not in capitalism’s thesaurus of possible synonyms or concepts. Instead, capitalism teaches and un-sacredly preaches (with millions upon googles of images, pundits, tik-toks, Murdoch Inc., etc.,) a propaganda so nearly perfect hardly any of us notice that we are breathing hot air. Nor are we able to question the assumption that we are fundamentally alone and that we must compete for material goods and status on a (hallucinated) level playing-field. No wonder so many of us become depressed, anxious, addicted, or psychotic, and privately believe that we are ‘losers.’

We cannot sell Love. It is the one thing that can never be for sale.

Lovers walk along the shore and leave their footprints in the sand

Is the sound of distant drumming just the fingers of your hand?

Today is the anniversary of the attack on the Capitol in Washington. Trump is down, but he will be back – we have not seen the last of him, or his ilk. His party, once that of Lincoln, has utterly disgraced itself. He or his daughter will be back in 2024, and our American sisters and brothers will need to be ready. Damage has been done to our Australian democracy from Trump’s example, and from the Murdoch media empire (suddenly, “Murdoch” reminds me of Moloch, the ‘god’ who demanded the sacrifice of children. Remember Ginsberg’s Howl ? ) Thus, from Canberra, the march towards death by fossil fuels continues, oh-so-very-slightly slowed in pace, and Ministers and Senators do not resign when shown to be corrupt. All over the world, totalitarian governments seem to be in ascendence.

Please read Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny because we may need to know his twenty points for resistance by heart, gut, and immediately.

I want to walk in the Botanical Gardens now. I think of white blossoms, falling, falling, covering me in their glorious impossibility, in their luminous softness. Suddenly, I see an impressionist painting by John Singer Sargent inside my eyes where children’s faces are brightened by the orange glow of lanterns, on a long-ago purple evening, somewhere in America.

Summertime/and the living isn’t so easy, without knowing how to love each other.

I read a letter from George Sand to Flaubert in 1871:

“And what, you want me to stop loving? You want me to say that I have been mistaken all my life, that humanity is contemptible, hateful, that has always been and always will be so?

…

When one sees the patient writhing in agony is there any consolation in understanding his illness thoroughly? …

Humanity is not a vain word. Our life is composed of love, and not to love is to cease to live.… Past grandeurs have no longer a place to take in the history of men. It is all over with kings who exploit the peoples; it is all over with exploited people who have consented to their own abasement.

That is why we are so sick and why my heart is broken.

… Let us love one another or die.

…. You want me to see these things with a stoic indifference?

No, a hundred times no. Humanity is outraged in me and with me. We must not dissimulate nor try to forget this indignation which is one of the most passionate forms of love.”

Everything that is wrong with the world, everything, is due to vicissitudes of love. All the hatred, racism, war, fear. All of these are secondary to power elites making sure we cannot love or connect in solidarity.

But what is to be done?

- Rosa Luxemburg knew. Many people know.

——————————————

Remember. Remember everything, our father said. We were two little children in our knickers on a hot summer’s day, our back garden loud with cicadas’ chirr, Meaghan and I running screeching with joy and the shock of sudden cold water on our skin as we ran through the rotating sprinkler’s moving reach, its slow, chh, chh, forward sound: the sudden, fast clacking back, staccato; the water making rainbows, arcing colour in the friction between sun, air, water. I stopped, noticing the sudden quiet seriousness of our father’s face – he had been laughing, a moment ago. – Remember, he said, remember everything. He was young: thirty-two, at most.

How did he know, at that age, that love and memory are joined? How did he know that remembering is a form of love?

Patti Smith knows it. When she loves a dead poet or a writer, she reads them over and over, and will eventually pay her respects at their graves. Smith’s Devotion is her book about the love in memory. My second name comes from a gravestone, which my child-parents found before the cemetery was demolished. The brown, roughly hewed stone had no dates, but said merely: This is E’s grave.

Against Forgetting is an anthology of poetry by Carolyn Forché, poems witnessing the wars, atrocities, and genocides of the twentieth century. Forché knows that to witness is to bear the unbearable with another and survive, as they did. And is an act of righteousness. It is proper. I pay my respects to the dead when I pick the book from the shelf, but I can rarely bring myself to open it. It is hard to bear witness: it is painful to remember history. But when we do, we uphold the truth. And truth is another form of love, or a love song:

Pictures hanging in a hallway, and the fragment of a song

Half-remembered names and faces – but to whom do they belong?

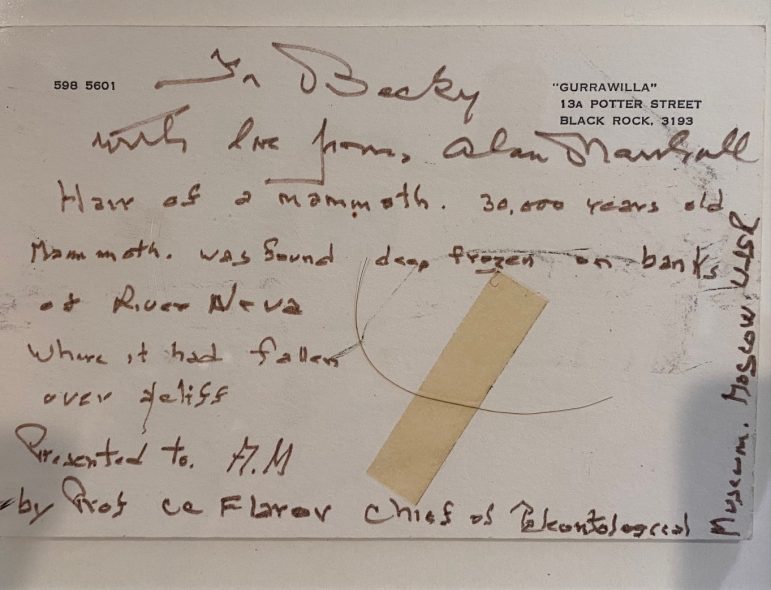

Alan Marshall, the author the sublime I Can Jump Puddles and How Beautiful are They Feet, and survivor of the polio pandemic, gave me this mammoth hair, sticky-taped on a card, when I was a small child. I’ve framed it, and it hangs not in a hallway, but on the wall over an oak table. I remember Alan, vaguely: a beautiful elderly man in a wheelchair.

We love what we know, and what we consciously and unconsciously know intimately. We recreate old loves, the goodness and badness inside each of our parents, when we partner with or marry someone. The relationship may be painful, sometimes extremely so, if as children we have not been loved well enough: but it is familiar, and it feels like home. No-one completely escapes their family – we contain inside our psyches one or two people at least, if not Whitman’s multitudes. And we love them until it is impossible to love them any longer: until we are patients (sufferers), and in transference-love or the ‘real relationship’ of psychotherapy, we are loved a little better, and learn to love ourselves more.

I fell in love with Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish socialist intellectual and revolutionary, the first time we ‘met’ in New York. Training in psychiatry there, I took a course in politics at night to distract myself from the suffering of patients and read a few of her essays, and of her extraordinary life. Born in 1870, the same year as Lenin, she foresaw what Lenin would do (e.g., promote nationalism over internationalism, laying the seeds for Stalin) and did her best to stop him.

Luxemburg: blessed with a brilliant, rigorous intellect, she was inspiring, loving, and optimistic. She was brave, tender, and wise. And she could be vicious to her enemies: ice-pick scathing, ruthless. So complex, and towards the end, so clear, and more and more joyful and loving.

Excerpts from a letter Luxemburg wrote to her friend, Sophie Liebknecht, in December 1917, while imprisoned for a third year in Bresalu for her pacifism and internationalism. It is a long letter about current political news, grief, encouragement, prison, and the oppression of human beings and animals. The italics & slashes, which make it read like a poem, are mine.

Last night this is what I was thinking: how odd it is that I’m constantly in a joyful state of exaltation

I’m lying here in a dark cell on a stone-hard mattress/

from time to time one hears…the distant rumbling of a train/

the entire hopeless wasteland of existence can be heard in this damp, dark night/

I lie there quietly, alone, wrapped in these many-layered black veils of darkness, boredom, lack of freedom, and winter – and at the same time my heart is racing with an incomprehensible joy, unfamiliar inner joy as though I were walking across a flowering meadow in radiant sunshine.

And in the dark I smile at life, as if I knew some sort of magical secret that gives the lie to everything evil and sad and changes it into pure light and happiness. And all the while I’m searching within myself for some reason for this joy, I find nothing and must smile to myself again – and laugh at myself.

…

I believe that the secret is nothing but life itself

Rosa is all around me as I write this tonight. Two of her books: Leninism or Marxism? And The Russian Revolution. Biographies. The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg: and scribbled quotes of her thought in pencil on scraps of paper.

She was barely over five feet tall and walked with a limp, her hip displaced as a child. (Did she wrestle with an angel one night, a tendon torn by morning?) A beautiful voice, sonorous, projecting easily across masses gathered in cobbled squares, and able to fill vast rooms of thousands of men (the Second Internationale meetings, for instance) and swaying them. Some would boo furiously at first: but there was standing and cheering, before she finished — even she could hardly be heard above the applause and yelling. Trumpeting shouts of hope and cheers for the possibility of possibility[2]. Cheering, praising, roars of joy of the justice-to-come. Over and over again, so many speeches. So many newspaper articles and pamphlets. When did she write them all?

She didn’t want to fight in politics, never wanted to be a politician or a revolutionary, but politics and revolution came to her. Already fluent in Marx as a teenage girl, already in danger for her political high school speeches, she smuggled herself across the border to Zurich for study – how she loved to learn, this Polish woman who spoke German as her first language: the tongues of sciences (botany and zoology, her first academic loves.) Then: philosophy, history, political science, and her doctorate in economics that is still studied today. She curated and held in her memory poems, novels, and songs. I had a picture somewhere – I’m sure saw it – of her holidaying at a lakeside beach with friends, bicycling there in the summer. She adored her cat, Mimi, labeled botanical specimens, and loved men: Leo Jorgiches was her great love and political partner for many years, and then a dear friend’s young son. Marveling and rejoicing in the existence of flowers, she made a garden in a prison yard during one of her many imprisonments, having befriended the superintendent.

Rosa, I say to her, sometimes on wild nights I feel the air is full of frisson, stars are impossibly falling, and the northern and southern lights sheer at once. Rosa: one day I stood in on Broadway on the Upper West Side, and felt something that sounds obscene in language, for it was a state of knowing beyond the reach of words — that everything, everything was somehow all right…it lasted only a few days, and has never returned, but it was a little like in the letter you wrote – a deep peace – despite and including everything: the poverty and screaming, the imperfect symmetry of flowers, death, love, war, and history. Life.

Rosa Luxemburg was forty-seven years old when she was murdered on January 15th, 1919, in Berlin, by the Freikorps – mercenaries who had fought in the Great War and were at a loss. They had suffered many losses, in fact: the war, their former selves. They lost morality and empathy (perhaps they were numb, or number than before the war, suffering Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder? Flashbacks, nightmares, attacks of fear and rage?) Many of the members of this paramilitary force went on to be important members of the Nazi party: Himmler, and Rudolph Höss (later the longest ‘serving’ commandant of Auschwitz.) A group of them dragged Rosa out of hiding in her hotel room that night, where she was reading Goethe, waiting to be found and imprisoned for her political action, as often before: so the long beating would have surprised her. And then the bullet to her brain.

The men with guns threw her into the water of the Landwehr Canal. I imagine her floating all that morally-blackened, bloody, and freezing night, her long dress a fan around her. But Rosa was not a suicidal Ophelia, maddened by a madder lover, held up by the water and her dress, surrounded by garlands of flowers: she was an assassinated political activist and public intellectual, killed because the government feared she would succeed in bringing forth from her heart and loving mind an irresistible newness.

Now I have discovered that the Freikorps weighted her body, so she sank in the canal. Rosa, did you rest on the mud at the bottom? Are you “at rest”? – But you never rested, so why would you now? Busy spirit, the world needs you now more than ever, more than when they killed you.

Thank God we have your books and your letters.

Like a door that keeps revolving in a half-forgotten dream –

Or the ripples from a pebble someone tosses in a stream.

Like a clock whose hands are sweeping past the minutes of its face

And the world is like an apple, whirling silently in space.

Reading once about her, I found a line like – “Rosa Luxemburg was defeated…” And I had an instant reaction: “Defeated? No! She wasn’t defeated, she wasmurdered.” Assassination is not the same as defeat. In fact, it’s a compliment of sorts – you’re really scaring someone with your love for what is right if someone assassinates you, as Martin Luther King, Jr., Gandhi, and many other killings would attest. Including: Robert Kennedy, Lincoln, First Nations leaders in Australia and everywhere else, whose names, unforgivably, I don’t know.

After a huge political defeat in California, thirty years ago, a small political group was devastated. Tears, disbelief, anger: smoking too many cigarettes, we were all heavy and stony with our grief as bad news came in. Michael, who had fought the hardest, designed most of the campaign, and dreamed its words, was near me. I turned and saw that he was quiet: saddened, but calm.

“How?” I asked. “How can you be so calm?”

“We’ve only been at this,” he said, “- this human rights, this justice thing – we’ve only been at it for a few thousand years.” And then, musingly: “It’s going to take a little longer.”

Michael Lerner was born in New Jersey in 1941. He was a Professor of Philosophy but lost tenure for his political activities. A leader of the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), the Free Speech Movement, and the Anti-war movement, he was one of the ‘Seattle Seven’ – for that he spent time in prison. He is now a rabbi, and we have long been friends. Today, he is in Berkeley – the city where he fought many battles – and has Covid: he’s so unwell he can hardly type. He’s written many books, the latest and most cogent of which is Revolutionary Love: A Political Manifesto. It’s practical and sensible, outlining a way forward.

Love is always revolutionary.

There is love in the letters I keep hidden in a nondescript box at the back of a high shelf, and in the ones I threw away. There are ‘love’ letters and cards from partners, friends, and people whom I can’t quite place anymore. And then there are those other ones on my bookshelves – the love letters (books) to us all from the world. Both types tell us we could – we must – be together, in Love, or in beloved community.

I sobbed for a moment and held back tears when I hid from myself in those boxes. ‘Youthful dreams’ of changing the world “one person at a time” as my psychoanalyst friend Gail says, but bless her, she’s wrong: we have to move faster than that. We need a socialism, or a post-socialism of love.

Do we see now that there were then powers which seemed too big for us, or who persuaded us that we are alone and at war with each other? They are trying hard again, now, always, to persuade us this of this lie, and they told and tell us so, again, and again, from every direction, until lies about our separation and competition seemed and seem – utterly real. Reality. Ontologically self-evident, built into the structure of how things are, human nature red in tooth and claw.

No. We are clawing and longing for revolutionary love. Just under the skin, we flow with red blood, through the four chambers of our hearts. We are slightly salty rivers, near the ocean’s wash when the tide comes in. Feel the pulse at your wrist and in your neck where our best angels kiss us: the beat, lub-dub, lub-dub, a timepiece of creaturely eternity in your chest. And the rise of warmth in your wise-animal-body when your heart is moved, and tenderness is near: these are truths, these are the evidence of who we are.

We buried, hid, and tossed into the flames precious jewels-of-longing, lest we seem foolish. Tossed and buried those dreams and loves away, in compliance. But the lonely heart is a hunter, and never completely forgets.

Changing entrenched social structures, changing the belief that this all is natural, is very hard, Lerner says – “but ‘very hard’ is different from ‘impossible’.” What a wonderful line.

We are remembering and finding what has been misplaced. A letter, mis-directed, just as some our acts have been, is returned to the right place: delivered. Deliverance.

There is hope: not naïve – strong, clear-eyed, sad, brave, and tender. There is hope in the love letters that are the books, poems, sciences, philosophies, fragments of lines, myths, essays, stories, and songs of experience. They were written long ago, sent in sea-tossed bottles, scrolls, songs – can you hear them? – across oceans, deserts, and wild waves of time. Or they are being written now, and tomorrow.

Circles in spirals can move upwards – upwards! – in ever-widening turns.

There is hope for our hearts, our bodies, each other, the body politic, and the earth: interconnected all. And so we begin, again.

[1] Donald Winnicott, an English pediatrician and then a most creative, playful, kind and yet serious psychoanalyst meant by this statement that a mother/caregiver and an infant cannot survive alone: they need the holding, the care, of another. And another. And another …

[2] Michael Lerner: one of his definitions of God