I have taught and written about socially conscious artists for almost a half century. When I began, I dealt almost entirely with iconic dead artists like Francisco Goya, Honoré Daumier, Käthe Kollwitz, Ben Shahn, Diego Rivera, and many others. More recently, my focus has been on African American artists, especially in the Los Angeles area. I explain to my students that the emotional calculus is different. These creative women and men are not merely subjects; they have become friends, even very close personal friends. And when they die, it hurts and I grieve.

John Outterbridge, a truly great artist, died on December 23. He was my friend for many decades and a friend and mentor to the entire community of Black artists in Los Angeles and to artists throughout the county and even the world. I wrote an entire chapter about him in Resistance, Dignity, and Pride, my first book about African American artists in 2004. John’s passing now makes it seven of the sixteen artists in that book who have died. I spent extensive time with all of them. I visited their studios and homes and they sometimes visited mine. Each death took a toll on me, especially when I explained my connections to my students. At times, I strained to keep control. This is real and this is personal.

John Outterbridge’s extraordinary accomplishments as an artist, teacher, and arts administrator are well known. His mixed-media assemblages, often constructed from found and discarded materials, including trash, fabric strips, and cloth, made him one of the premier artists of this tradition. Like Noah Purifoy, John Riddle, Betye Saar, John Riddle, Tim Washington, and a few others, the assemblage efforts born in the wake of the Watts rebellion of 1965 reflected the brilliance of Black visual creativity. Those efforts likewise gave these African American artists the opportunity to use their work to call dramatic attention to the plight and grievances of Black people in Los Angeles and throughout the nation.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

John Outerbridge was a visual archeologist and griot who often rose early in the morning to collect “trash” and “junk” for his creations. Those excursions enabled him to listen to the conversations of older residents of African American communities, fortifying his appreciation of their struggles and achievements. He even incorporated yams and other organic material into his work, extending his commitment to discovering and communicating the roots and branches of a people generally ignored in American history because of their African origins.

John’s early life in North Carolina emerged from a loving family that always encouraged his creative energies, including painting and singing. His mother was a poet and a pianist. During his long artistic career, he produced artworks honoring both his mother and his father. A striking example is his 1993 artistic homage to his mother. “First Poet, Olivia” (Figure 1). This mixed media installation, topped with seven realistic looking irons, is a tribute featuring an imaginative ironing board honoring the years of domestic work that his mother and millions of women of all races and nationalities performed. This artwork is especially significant in its early feminist consciousness and in its African American commitment to strong family values, in stark contrast to the destructive attitudes about Black families that some national journalists and prominent political leaders disseminated in recent decades.

Like everyone in his generation, especially in the South, he encountered the pervasive racism of the Jim Crow era. He was called racial slurs and witnessed the extreme discrimination that denied African Americans opportunities to pursue dreams and ambitions. But he also experienced the vibrant culture of barber shops, domino groups, and churches that formed the basis of Black life in the segregated South in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s.

After military service and eight years in Chicago, where he both received formal artistic training and worked as a bus driver, John moved to Los Angeles in 1963 where he forged his international artistic visibility and reputation. He soon became involved with the vibrant African American art community, including some who went on to become major international figures themselves. Together, they formulated strategies for using their art as a tool for social change. This became a hallmark of John Outterbridge’s work for the remainder of his long career.

He also became a distinguished teacher and administrator in the Los Angeles area. He was a co-founder and art director of the Communicative Arts Academy in Compton. The Academy was a major gathering place for the Black community and a unique institution to foster creativity in many fields for young artists. His most prominent contribution as an arts administrator was his directorship of the Watts Towers Arts Center, a venerable community institution adjacent to Simon Rodia’s landmark towers. The Watts Towers Arts Center has served minority communities magnificently, with educational programs and music festivals, for more than fifty years and John played a powerful role in making it a central arts institution in Los Angeles.

I had the great privilege of speaking with him extensively over the years. He was a powerful orator and storyteller. When I brought my UCLA students to his South Los Angeles studio for field trips, he would mesmerize them with his stories. He would show them his own artworks as well as those of so many of his African American artistic contemporaries. They were memorable experiences for my students.

John Outterbridge Mixed media assemblage construction Mixed media

Collection of the California African American Courtesy of the California African American.

Museum. Gift of the Artist. Collection of the African American Museum

Foundation. Gift of the Artist.

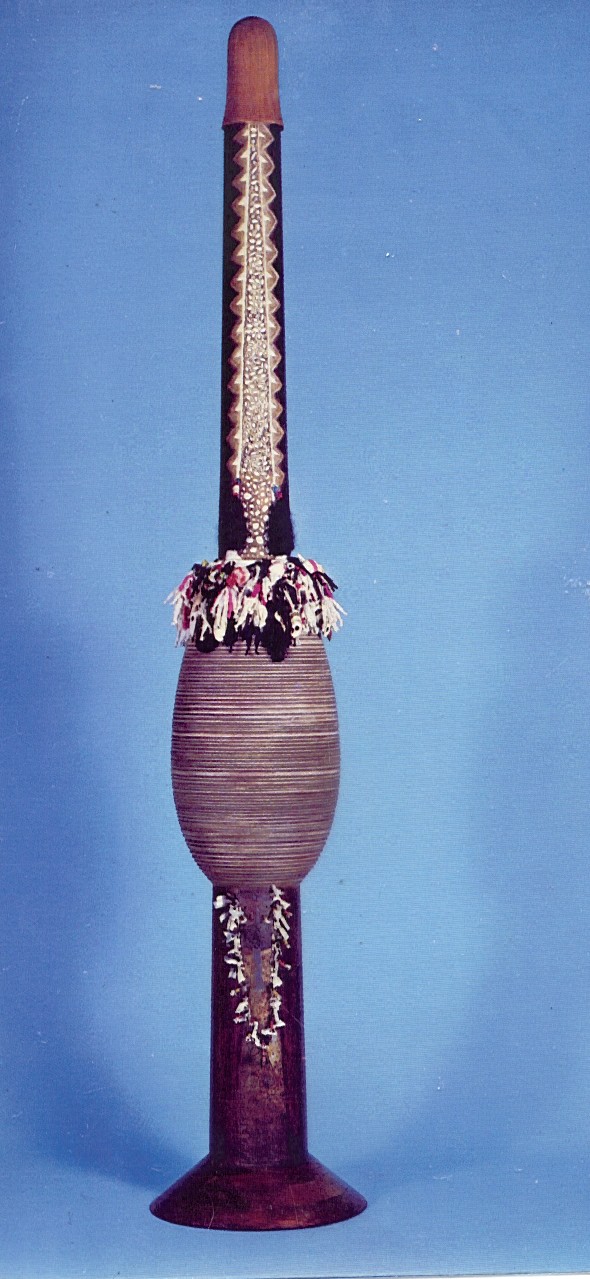

I also took students to visit his retrospective exhibition that ran from August 1993 to May 1994 at the California African American Museum in LA. One of the premier works in the collection there is “Lift Every Voice” (Figure 2), a gigantic 11-foot flute he created for the inauguration of the Museum in 1984. This monumental artwork, constructed from wood fragments, extends the ancestral theme that is so vital in the entire tradition of African American art. Outterbridge, like so many of his artistic predecessors and contemporaries, used his work to call attention to identify and honor his ancestors––a heritage that centuries of slavery and Jim Crow had tried to obliterate.

With the title derived from an old Black spiritual, (and James Weldon Johnson’s adaptation of the Black National Anthem), the work also calls attention to an African musical instrument, symbolizing its inextricable connection to the music of the New World Black population. The aggressively African decorative elements of the flute suggest John’s commitment to recapture a long-concealed heritage––a vision he expressed frequently to me during his long creative life. In urging his fellow African Americans to explore their African origins, he followed the thematic path of many Black artists since the Harlem renaissance. And in celebrating the enormous impact of Black music, “Lift Every Voice” adds a unique expression to this recurring focus of the Black visual tradition.

In my class, and often in personal conversations, I remarked that if John Outterbridge had been white, the 1993 retrospective exhibition would have been held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York or some comparable institution many decades earlier. When I served as co-curator at the massive 2011 exhibition of African American art at the California African American Museum in conjunction with the Pacific Standard Time series of shows, we highlighted John Outterbridge among other visual art luminaries.

Twelve years ago, I sought to augment his many awards and honors by seeking his appointment as a Regents’ Lecturer at UCLA. This is a complex bureaucratic process demanding that a nominee meet this high standard: “distinguished leaders from non-academic fields to enrich our instructional program and increase students’ exposure to a diverse range of successful professionals, artists, and others.” John met this standard easily and went on to speak to various UCLA audiences with his customary eloquence. He continued to reveal his remarkable talents as a storyteller and reinforced his reputation as a modern-day griot.

John Outterbridge was closely involved with every institution in the Los Angeles region devoted to African American visual art. In 1967, artists Alonzo and Dale Davis founded the Brockman Art Gallery, which featured many of the most iconic Black artists throughout the country. The Gallery also featured outstanding Black artists throughout the LA region, including the Davis brothers themselves as well as John. The Brockman Gallery was pivotal in making African American art a visible feature of the exploding art scene in the area. It was crucial in facilitating the impending Black artistic renaissance. As John told me perceptively in 2008, the Brockman Gallery “was the museum before the museum,” referring to the subsequent creation of the California African American Museum.

Throughout his long career, John produced such an abundance of artwork that it becomes an impossible task to select any personal favorites. But I have two that stand out because they resonate so effectively when I show them to my students. They reflect John’s enduring commitment to using his art for incisive social and political commentary, another profound hallmark of African American art for well over a century. They also speak powerfully to me because of my long personal history as a civil rights activist. Art is personal and I have urged my students and my readers over the years to link their contact with visual art to their own lived experiences.

In 2003, he created “Outhouse” (Figure 3), a large wooden structure with two wheels mounted on the exterior rear sides. On the inside are text, photographs, a light, and an audio recording. On the outside are stenciled dates. This remarkable mixed media assemblage was shown at the California African American Museum in conjunction with its 2004 “Through the Gates: Brown vs. Board of Education” exhibition.

“Outhouse” is an amazing artwork. Above all, it highlights the marginal status of millions of African Americans through the South for so many decades. When I was doing civil rights work in places like Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana in the early 1960s, I often saw Black homes without indoor plumbing, especially in rural areas. These structures were––and are––emblematic of the huge racial and class divide in America. As a child, John often saw these structures in North Carolina and it helped galvanize his later commitment to using his art to tell the story of his people.

The text on the outside side of the outhouse is revealing. Two dates particularly stand out: 1896 was the date of the notorious U.S. Supreme Court decision of Plessy v. Ferguson, which by creating the “separate but equal standard” institutionalized Jim Crow segregation for more than fifty years; and 1954 was the historic Brown v. Board of Education decision, where the Supreme Court outlawed school segregation and effectively overruled the Plessy decision. Inside the structure are images of the Klan, civil rights protests, and the text and comments on the Brown decision. The wheels symbolize the potential of African Americans to move forward, a phenomenon we all saw with the massive protests in the wake of the horrific murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and too many others last year.

“In Search of a Missing Mule”)*, which he created in 1993, is a provocative and deeply unsettling effort. The missing mule represents the nation’s failure to deliver on its post-slavery pledge to provide forty acres and a mule to former slaves, a symbolic source of the economic disadvantage of millions of contemporary African Americans. Drawing again on his Southern past, he recalled vividly how rural Blacks established relationships with their mules, emotional bonds that reflected the intensity and quality of life on the land. The government’s refusal to provide mules to former slaves exacerbates their feelings of betrayal and helps explain their continuing distrust of white power generally.

This powerful artwork is deliberately unsubtle. Although its strong steel figure resembles the Statue of liberty, its portrayal of American values and practices contradicts what this American icon supposedly represents. Instead of promoting uncritical patriotism, the work encourages viewers to question the myth of a glorious past and a racially harmonious present. At its left, facing viewers is a yoke for the mule, still unused. More ominously, at its right, is a noose, a disconcerting reminder of the tragic fate of thousands of African Americans.

John and I spoke often about this this sculpture. I told him what I regularly tell my students about it: “Still no mule and still no forty acres.” John told me that his fantasy was to walk a mule through the streets of Los Angeles, a symbolic gesture to remind its citizens how America has defaulted on its promise to its citizens of color.

The tragic events of the past year only underscore the force of this remarkable work. Public attention to the deep racism of American police has also brought welcome inquiry into the racist structure of American institutional life generally. John was isolated from the community for quite a while before his passing, but I know that he must have been pleased with the outpouring of protests through the U.S. and the world this past summer. And I know too that he would have been pleased had I been able to tell him that I was a participant in many of these protests.

I have lost a friend and the world has lost a magnificent artist and a beautiful man.

*Despite repeated attempts, I was unable to reach the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Permission and Reproduction Department, which holds the right to this remarkable image; therefore, I regret severely that I am unable to include it.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

Professor Von Blum,

Thank you for this beautiful and expansive article and remembrance of John Outterbridge. It. captured the spirit and breadth of his life.

Our family knew him as a friend and colleague over the decades.

We are grieved over his passing.

“May the good he left last forever”

Jackie Ryan