God gave all men all earth to love,

Rudyard Kipling

But since our hearts are small,

Ordained for each one spot should prove

Belovèd over all.

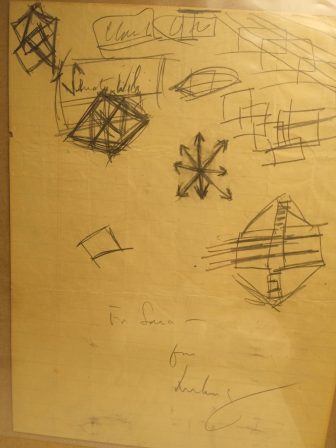

Hidden in the back of various cabinets through the years, as life has taken me from one country to another and from place to place, are stored for safekeeping three items given to me in childhood by my father, the writer and editor Norman Cousins: the originals of two black-and-white news photographs from 1963, taken a few moments apart at a meeting in the White House, and one scribbled-upon piece of paper, torn from a yellow legal pad and inscribed, “for Sara,” by the President of the United States.

Though the items are lodged securely in the back of my mind, on occasion I’ve forgotten where it is I last put them, invariably triggering a frantic searching through papers and drawers and files, to make sure they’re still in there, beyond children’s–and now grandchildren’s—inquisitive hands. In one photograph, we see my father looking happily down over John F. Kennedy’s shoulder as the President, at his desk in the Oval Office, signs the page of darkly-penciled-in doodles that my father had noticed him drawing during the meeting; and inscribes it–as my father has requested–to Norman’s little girl, back home in Connecticut.

In the other one, a smiling JFK rises from his chair, paper in hand, and my father, in the background now, tips back his head with a joyful laugh. The gesture was characteristic; it didn’t take much, at any time, to make my father celebrate. But his laughter on this occasion was unique, and uniquely profound. For his labor of love—devotion and love for his family, and (without exaggeration) for human beings everywhere, and for the miraculous, tiny blue speck in the cosmos upon which we find ourselves–had at last borne fruit. After a year of painstakingly sensitive, complex negotiations for which my father had served as an intermediary, a historic agreement had been reached between President Kennedy and Russia’s Premier Nikita Khrushchev, to ban further nuclear testing in space, in the atmosphere, and underwater.

The treaty still had a long way to go; ratification in the US Senate was not going to be easy.

But for now they were jubilant.

The Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, or LTBT, was not the comprehensive agreement that my father had sought, especially in light of how close to nuclear war the two countries had come during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The fact that a ban on underground tests had not made it into the agreement meant that the signatories were left with lethal wiggle room, which would prove, indeed, to be a deadly loophole exploited—for the most part by Russia–for years to come.

But this was July 1963, and the Treaty, thought my father, was a good first step. It went as far as the two nations’ leaders could go, at that juncture, without arousing overwhelming opposition from their respective militaries. And one of its most important achievements, he thought, was its impact on public perceptions. Nuclear weapons, nuclear proliferation, nuclear war….the topic tends to induce fatalism and resignation. It’s not in my hands. But it was as a private citizen that my father had been involved, and the Limited Nuclear Test Ban to which he gave his all is, in fact, still in place. It was, he believed, each and every human being’s personal responsibility to take care of this world. MAD—pop slang for Mutually Assured Destruction—doesn’t have to come true. Global suicide is not inevitable.

Some other people, too, appear in those photographs, but it’s only now, while writing this story, that I’ve realized something odd: in all the decades since I sat down at the table for breakfast one summer morning and found at my place two pictures of Daddy and a page full of scribbles, and looked up to see my mother standing there with a little smile, awaiting my response, I’ve never bothered to find out who those other men were. In the opinion of my inner child (who to this day is still in the majority on numerous issues) those other people weren’t The Important Ones.

But for that matter, as I saw it, neither was I. I was the baby in the family. It was a fact of life. Among my older sisters and their teenage friends, and among all the tall, often wrinkled adults from all around the world who passed through the guestroom in our Connecticut home, I took my unimportance for granted. And naturally I was resigned, as well, with equal parts wonder and anxiety, to my insignificance in the huge, indifferent, unsupervised universe, with all its thousands of stars and planets hanging around at random without explanation, in the emptiness of outer space.

When, in 1955, my father’s magazine arranged for twenty-five young survivors of Hiroshima to be brought to the United States for plastic surgery and other medical treatments, my sense of helplessness turned sinister, and took deeper root. The Hiroshima Maidens, as they came to be called, had been scarred and disfigured and wounded in myriad ways, both visibly and invisibly, in the radioactive firestorm, and I assumed it was just a matter of time before it happened to us. I recall telling my father, with a child’s plainspoken simplicity, that I knew I wouldn’t live to age 20. I wouldn’t get married, I said, or have children. The Bomb would fall before I grew up

The Maidens were settled in various American homes for the duration of their treatment, their travel and hospitalizations having been sponsored, in response to my father’s appeal for contributions, by subscribers to his magazine. Readers of his Saturday Review editorials shared his sense of personal responsibility for our country’s having been the first to introduce nuclear war into world history, incognizant of its utterly unprecedented dangers, extreme dangers which would one day rebound upon our own People, and our children, and our children’s children. With our scientific prowess, we had perverted the miraculous, infinitesimal building block of Creation into a weapon of war that could extinguish Creation.

“It is an atomic bomb,” President Truman had announced proudly to the Nation upon Japan’s surrender 13 hours after the A-Bomb was dropped. “It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the Sun draws its power has been loosed against those who brought war to the Far East….The successful splitting of the atom” he said, has brought about “a new and revolutionary increase in destruction.”

One of the Maidens settled with us, at our home in Connecticut, and stayed, becoming a member of our family. She was covered with burns from head to toe.

The Bomb wasn’t some sort of distant rumor, or science fiction.

One cozy winter day, Shigeko and I were sitting dreamily before the fireplace when more to herself, perhaps, than to the little girl at her side, she said, “What you feel if you a small, small ant in that fire?”

We were gazing together into the flames.

“I was ant,” said Shigeko.

It’s my guess that like some of my father’s other books having to do with nuclear weapons, In Place of Folly, written in 1961, didn’t make it onto anyone’s bestseller lists. People generally don’t want to be told that

….there is no disagreement that poisonous strontium locates itself in human bone, where it is stored; that poisonous radioactive cesium locates itself primarily in human muscle; and that poisonous radioactive iodine has an affinity for the thyroid gland….There is no disagreement about the fact that strontium 90 can produce bone cancers and leukemia in human beings; that cesium 137 can cause serious genetic damage; and that Iodine 131 can cause acute glandular disturbances.

As a direct result of nuclear tests, detectable quantities of strontium 90, cesium 137, and iodine 131 can now be found in virtually all foodstuffs. Among these foodstuffs, milk is considered of exceptional importance, both because it is a prime source of nourishment for children and because it serves as a collection center for poisonous radioactive strontium. Detectable traces of radioactive strontium, radioactive cesium, and radioactive iodine have found their way into the bodies of human beings all over the world.

Strontium 90, cesium 137, and iodine 131 are produced in nuclear explosions. These radioactive materials do not exist in nature. They are entirely man-made….Human beings did not have [these] in their bones or glands or muscles before the age of nuclear explosions. This is new hazard in human history, completely man-made and so far, extremely difficult to counteract.…

All peoples are affected by the explosion of nuclear weapons, and not merely the people of the country conducting such experiments. There is no known way of confining the fallout to the nation setting off the bombs, nor is there any known way of cleansing the sky of radioactive garbage.

Permission from those affected has not been sought. Representation has not been offered to people whose crops were dusted with radioactive materials, whose cows have grazed on lands carrying a radioactive burden, whose children have drunk milk containing strontium 90 and cesium 137, whose leukemia rate has increased with the increase of radioactive materials in the air, and whose future carries a question mark to which no one has a precise answer. …To a mother who has lost a child, the universe itself has suddenly become a void. The child is not a statistic. To the people of a country who learn that they now belong to the first generation of men in uman history to carry radioactive strontium in their bones, the stark indifference of testing nations is incomprehensible and outrageous.

A ban on nuclear testing, with machinery in place for verification and enforcement, represents the best chance of keeping nuclear weapons from becoming standard items in the arsenals of the world’s nations.

I‘ve never been sure if my father actually articulated the line, optimism is realism, or if it was a conviction conveyed through his deeds, by the way he lived. One can be excused for wondering how his gift for positive thinking, for which he’s best remembered in relation to recovery from illness, can be reconciled with his incessant preoccupation with nuclear destrution.

I don’t recall with which fascist ruler it was that my father was once talking, having been sent by the US government to try to persuade the man to discontinue whatever brutality it was that he was then committing (I think it had to do with a political prisoner) when the man got quiet for a moment. And with an almost childlike curiosity, he asked, “Why should I?”

Whereupon Daddy looked him in the eye and said, “Because it’s the right thing to do.”

And taken aback, the brute complied.

It was my mother who told me that story, the night Daddy died.

My father had too much experience, negotiating with tyrants, to be accused of naivete.

In November 1963, a month after the Treaty was ratified by the Senate, President Kennedy was assassinated. I remember my father’s grief in that era, and remember how, with time, he willed himself to prevail over his despair. He resumed working towards a comprehensive test ban, although now neither America’s new President, nor Russia’s newly installed hardliner (brought in to replace the ousted Khrushchev,) was welcoming his efforts.

In the summer of 1964, my sister and parents and I were on a plane leaving from Leningrad, where my father had chaired a conference between American and Russian writers, poets, and scientists, when suddenly, minutes after takeoff, Daddy fell ill. The illness quickly disabled him. It was strange, and prolonged. His doctors at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York didn’t expect him to survive. He would later write in Anatomy of an Illness about the role of laughter in his recovery, but he chose not to divulge one of the details: his doctors had found in his body a bolus filled with streptococci, typical in cases of deliberate poisoning.

Were my father here now, I would ask him if his encounters included people in whom no inner spark of moral conscience could be uncovered. I’d ask him if the faith he demonstrated in the potential for goodness in every human being, was a pose he adopted for his noble purposes, to awaken whatever could be awakened in the other.

“No battle,” he said, “is ever really lost.”

Among his letters that I reread after his death was a handwritten penciled note: “All Earth to Love — possible title for book.”

I once heard it said that every person climbs one ladder throughout his life, designed uniquely for that person and no other. The person climbs and falls, falls and climbs, and climbs again.

Recently, another version of this idea came my way: that if one is repeatedly faced throughout one’s life by a particular challenge, then it’s safe to assume that it’s in this challenge that one’s mission in life can be discerned.

My ladder can’t be my father’s ladder. Not only because he is he and I am I, and nobody’s asking me to go talk to Putin, but because while I do have faith in the fact of a Divine Purpose in our struggles here on earth, faith in mankind is not my forte.

As nuclear-armed powers fight a brutal war in Ukraine, and as North Korea, which last exploded a nuclear test in 2017, brags of its nuclear arsenal…as China flexes its nuclear muscles…and Iran openly seeks to develop its nuclear capability, specifically with an eye on war with Israel, I miss my father. The Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty he worked so hard to negotiate still stands, but its full flowering which its signatories had in mind was cut down by the machinations of men.

My claim to fame is not that President Kennedy, who didn’t know me, wrote my name and his on the same page, though his eloquently tense doodles are dear to me. It’s that in my father’s sweetest moment of joy and triumph, when for a fleeting interval his mission in life seemed close at hand, he remembered me.

Though he was by necessity that day far from home, his fatherly love planted itself in my mind and told me that I matter.

Though it’s my family, my home, my country, that my mortal heart most loves, I want to do as my father said. I want to take my share of responsibility for the survival of our beloved world.

So I’ve written this story, and raised my small voice to the One in power.