Stony The Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Penguin Press 2019, 296 pp.

A new book by the amazingly prolific and accomplished African American scholar and public intellectual Henry Louis (Skip) gates is a major event. The author and co-author of more than a dozen books about African American literature, history, and culture and editor and co-editor of some hugely important reference volumes including The Norton Anthology of African American Literature; Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African Experience; and The African American Biography, among many others, Gates has made profound and enduring contributions to American intellectual life.

He has likewise helped establish African American Studies as a respectable academic discipline and has brought genealogy into the American mainstream with his PBS series “Finding Your Roots.” His other television documentaries have also shown that at least a few intellectuals have a serious place in popular culture. His highly publicized and absurd 2009 arrest for allegedly breaking into his own home in Cambridge, Massachusetts thrust Gates into major public prominence, especially after President Barack Obama said that the Cambridge police “acted stupidly.” The charge, of course, was swiftly dismissed. Obama’s famous “beer summit” largely put the controversy about that egregious instance of racial profiling to rest.

Still, even though deeply admiring and respecting Skip Gates, and even having met him and contributing to The African American National Biography, I always wonder about his obvious comfort level with establishment liberal politics. I wonder too about his easy movement in African American elitist circles––much like his friend Obama and others in that community who seemingly have entered the black professional class with considerable distance from the large majority of their less privileged women, men, and children of color.

I don’t know whether Skip Gates and other prominent Black intellectuals were so enamored of Barack Obama simply because of his blackness. They seemingly ignored Obama’s capitulation to the ruling capitalist class while he largely neglected any serious conversation and discourse about race in America. I’m also mystified why Gates seemed to revel in his closeness to power during that time, without “blowing the whistle” on the major failures of the Obama Administration throughout its eight years in the White House.

The large majority of African Americans continue to suffer from intractable poverty, inadequate health care, housing, education and other vital services. All of these reflect historical and continuing institutional racism, a reality that has generated increased public awareness in early 2020 following massive public protests against egregious police killings of unarmed Blacks. Many other Black upper middle class professionals, especially younger African American academics (not all or even most, of course) also fall, I think, into that category, perhaps unknowingly, into a pleasant cocoon of academic respectability and status. They sometimes forget their sisters and brothers without their status and public visibility. That and similar critiques are fair enough and I have included Gates and some of his high level colleagues in that category from time to time.

My initial hesitation about the book and about its author, however, was quickly dissipated. Stony The Road is a powerful indictment of America’s racist past and a provocative vision of the failure of American institutions to address the original sin of slavery. The volume blazes exciting new paths in integrating extensive visual imagery into its historical narrative, a perspective that contemporary and future historians would be wise to emulate. This feature of Stony The Road, in fact, enhances its appeal to a general readership that goes far beyond a narrow scholarly audience.

The Civil War in America ostensibly brought an end to slavery. At a strictly legal level, that was true. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution is clear and unambiguous: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude …shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” In practice, all that provision did was to eliminate the formal ownership of human beings; it did nothing to ameliorate their actual economic and social conditions, even, for the most part, during Reconstruction. Law does not exist in a vacuum and the 13th Amendment did nothing to address the system of sharecropping on plantations and farms that kept former slaves and their descendants in an oppressive state of peonage for decades, making the abolition of slavery far less significant in starkly human terms.

Gates addresses the powerful and disgraceful Southern white resistance to real Black emancipation and the seemingly intractable commitment of all too many white Southerners to the “Lost Cause” mythology, the absurdly racist view that the Confederacy was a heroic battle against “Northern aggression.” One of the author’s most valuable contributions is to show just the deep racist historical roots of our national history. Even before the Civil War, slavery adherents used pseudo-scientific justifications to justify the enslavement of millions of people of African origin. Frederick Douglass, as Gates reveals, attacked the “scientists” and doctors who purveyed this dangerous nonsense.

Journalists also joined in this repulsive crusade. The book provides several examples. One is from John M. Daniel of the Richmond Examiner in 1854: “The true defense of slavery is to be sought in the sciences of ethology and natural history. The last defines the negro to be the connecting link between the human and brute creation. . . .Again and again we repeat it, the negro is not the white man. Not with more safety do we assert that a hog is not a horse. Hay is good for horses, but not for hogs. Liberty is good for white men, but not for negroes.”

I have recently used these quotations from Stony The Road in my UCLA class on Race, Racism, and the Law to show racism is embedded in American culture and history––and has resonance even now, especially in these times of anti-racist national and worldwide protests. That feature of embedded racism complements American legal history, especially the initial Constitutional provisions favoring and advancing slavery, in ensuring centuries of racist attitudes and practices among the white majority population.

Lest some contemporary Americans think that all of these were regrettable pre-Civil War phenomena, Professor Gates demonstrates convincingly that this cultural racism continued well afterwards through both “scientific” and visual expressions. Scientific racism continued well into the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The eugenics movement found strong adherents among “respected” scientists and universities. Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Virginia, and other institutions were at the forefront of promoting “scholars” who created racial hierarchies that elevated whiteness and denigrated African Americans. Gates is candid in singling out Harvard, his personal academic home for the past 28 years, as the major center of this racist phenomenon.

One of the most intriguing features of Stony The Road is its extensive inclusion of visual sources. The white backlash to Black Reconstruction took many forms, including powerful visual elements that infused American culture for decades from the mid and late 19th century through the 20th and even into the 21st. Political cartoons and posters abounded that included well-known and highly offensive racial caricatures of African Americans. Exaggerated lips and stupid expressions all reinforced the majority opinion that Blacks deserved subordination to the dominant race.

Gates also chronicles other visual features of Black stereotypes, including happy “darkies” singing and dancing and the more pernicious imagery surrounding miscegenation that shows the inevitable decline of the white race if intermarriage is permitted. This fear was widespread in the white population and inflammatory pictures only exacerbated the deep-seated historical aversion against people of African origin.

He also includes perhaps the most disturbing visual imagery of all: photographs of black lynchings. Some of these, disgustingly, were disseminated as postcards distributed across the nation as celebrations, mirroring the actual murderous events themselves. Historians can never be certain about the precise number of human beings lynched between the end of Reconstruction and the 1950s. The number of Black men, women, and even children extra-judicially murdered is in the thousands. Recently, the Equal Justice Initiative, founded and directed by Brian Stevenson, documented nearly 2,000 more confirmed racial terror lynchings of Black people by white mobs in America than previously detailed.

These photographs have been around for a long time. The most dramatic example is in the volume Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America from 2000. Those unnerving photographs are nevertheless valuable but painful educational documents, which I have used effectively for many years. Professor Gates also uses a few of them to augment his deeper message about the power of pictorial imagery to reveal the depth and horrors of American racism.

Perhaps the most striking visual features in this book are and the toys, postcards, theatrical posters, minstrel shows, and, above all, the commercial advertisements featuring stupid looking Blacks hawking various products. These were ubiquitous and have likewise been around and examined in the scholarly literature for a long time. I have written and taught about these repulsive images for many decades, often prefacing my presentations about African American Art with several examples.

Gates uses both well-known and lesser-known examples from the seemingly endless reservoir of racist visual culture. He includes familiar tropes like “coloreds” and watermelons, alligators biting and even consuming Black people, “Sambo,” blackface pictures, exaggerated black children portrayed as small savages, and the like. Not surprisingly, examples from D.W. Griffith’s racist classic film “The Birth of a Nation” also appear in the book. He doesn’t hesitate to include examples that employ vile racist slurs like “darkie,” “coon” and even “Nigger” (The Mischievous Nigger, play announcement; Jolly Nigger Bank, product; Hit the Nigger Baby, special event poster). Gates well understands that this repulsive language is contextual and such slurs here are essential to the book’s overall presentation and central argument.

Readers may find some of the commercial products most familiar. Figures like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben have pervaded American popular culture for many decades. Aunt Jemima: “All you need for perfect pancakes” and Uncle Ben: “Always cooks white and fluffy”: combined with their smiling black, yet totally friendly, reassuring and above all non-threatening faces, these iconic characters have allowed white Americans to believe in Black servility for generations. Their durability is legendary.

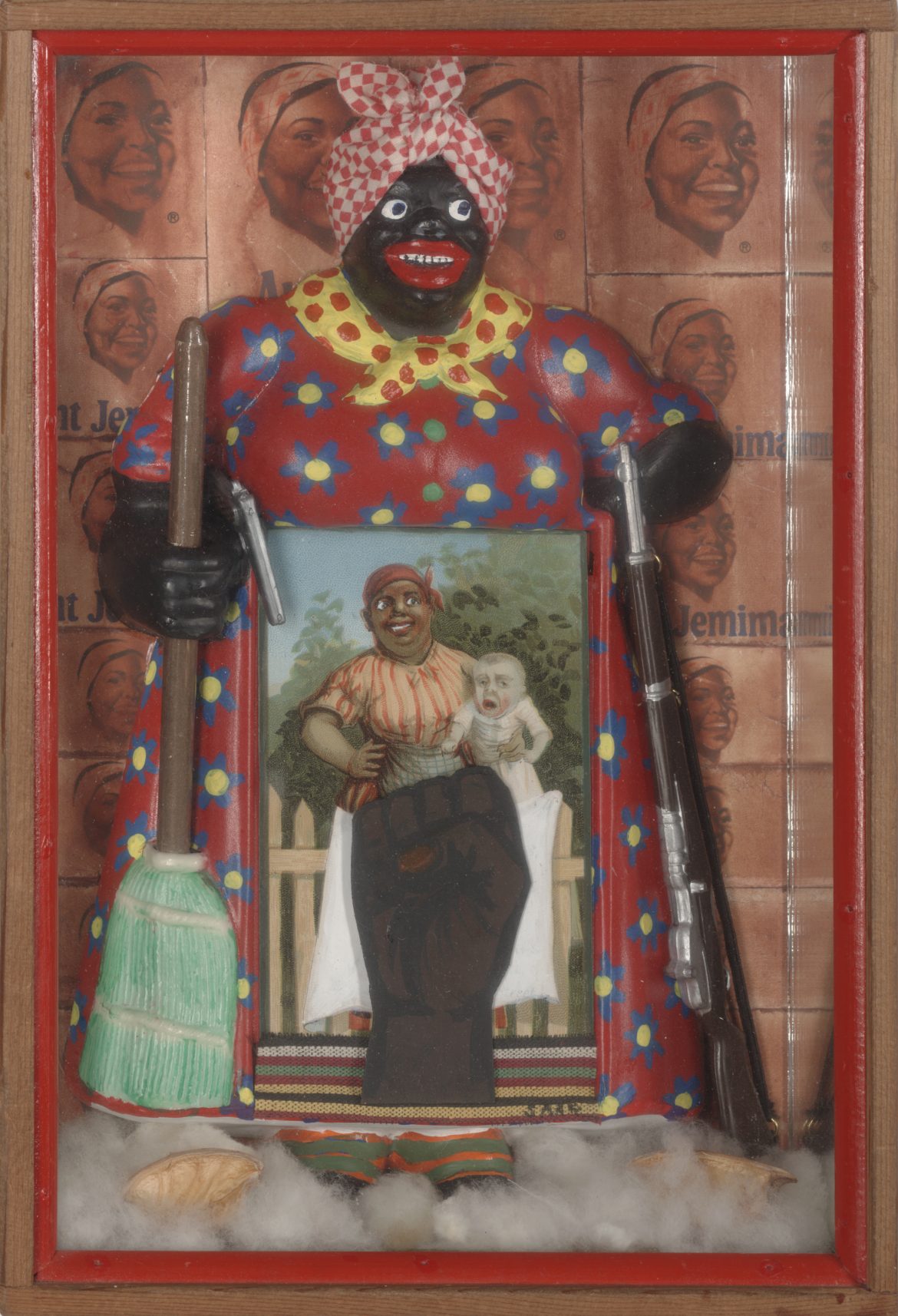

Until fairly recently: In the 1960s, many African American visual artists like Murray DePillars and Joe Overstreet mounted an assault on these derogatory images, especially Jemima. Perhaps the most famous is Betye Saar’s 1972 “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima.” There, the iconic artist created a powerful message of resistance. She placed a background of repetitive images of the modern Aunt Jemima, a slimmed-down and less burlesque version of the longtime commercial symbol for pancake mix. Saar’s picture in front is the old Jemima, the fat and sexless stereotype shown holding a mulatto baby. This image was typical of the portrayals of black people as dark, childish, and happy, fully content to serve their white superiors and absolutely cheerful about their subordination in American society.

Betye Saar placed a broom in one hand and a rifle in the other. Not yet truly liberated, Jemima was caught between traditional racial and gender roles and the emerging transformation promised by the militant social protests of Black people in America. Her weapon signifies that the time has come to cast off servility and join the struggles of her sisters and brothers. And in 2020, following the huge protest throughout the nation, Quaker Oats announced that it would retire the Aunt Jemima brand “to make progress toward racial equality.” Ninety three-year old Betye Saar noted that “[f]ifty years later, she has finally been liberated herself. And yet, “more work still needs to be done.”

Henry Gates concludes his powerful book with a major segment on The New Negro. This is an informative and engaging account of the various responses of the African American community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to the collapse of Reconstruction and the institutionalization of Jim Crow segregation, formalized by the 1896 racist Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson creating the “separate but equal” standard. He highlights the approaches––and key differences and conflicts––of such major figures as Booker T. Washington, W.E. B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, A. Philip Randolph, and Alain Locke, among many others to the continuing struggles of Black people in a white racist society.

This intellectual terrain, to be sure, is extensively covered in scholarly and popular literature. But Gates’s perspective on intellectual history in this volume is a strong addition to this literature and should properly command attention from scholarly and lay audiences alike. He does, I think, an especially valuable job in addressing issues of culture in these debates among Black political and intellectual leaders.

One useful focus is his treatment of Du Bois, who long attempted to counter the negative images of his people in his writing. Beyond that medium, Du Bois also sought other expressive forms to show the dignity of American Blacks. In April 1900, he presented the Exhibit of American Negroes at the Paris Exposition. The exhibition revealed a large selection of well-dressed African Americans of all skin tones, hair textures, and facial structures in various positions and roles of accomplishment. Du Bois also included images of libraries and laboratories, all signifies of the New Negro. Above all, these were dramatic pictorial repudiations of the harmful visual stereotypes of blackface, Sambo, Aunt Jemima, and so many others.

Stony The Road also addresses Du Bois’s concept of the Talented Tenth. Clearly elitist, this concept nevertheless gave visibility and respectability to African American poets, novelists, painters, and other creative persons who stood at the vanguard of creativity. A major example was painter Henry Ossawa Tanner, whose masterpiece 1893 work “The Banjo Lesson” featured an older man patiently and sensitively teaching his grandson how to playa difficult musical instrument. This iconic African American artwork focused on a loving transmission of knowledge––a dramatic and effective repudiation of the racist caricatures polluting the America cultural landscape.

This remarkable Renaissance of Black artistry, as Professor Gates shows, still must be seen in light of the more ominous events of the times. In 1917, racial violence exploded in East St. Louis, Illinois, resulting in more than 100 African Americans killed at the hands of white marauders. Poet and political leader James Weldon Johnson characterized the white mob attacks and lynchings of Black veterans of World War I in Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Elaine, Arkansas as the Red Summer of 1919. These horrific acts of violence were denounced by W.E. B. Du Bois and memorialized in the memorable poem “If We Must Die” by Jamaican-born Claude McKay. Massive pogroms in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921 and Rosewood, Florida against vulnerable Black populations only exacerbated this horrific overt post-Reconstruction American racism.

The book’s treatment of the Harlem Renaissance is exemplary. Gates identifies Alain Locke as the principal architect of this powerful, even exhilarating, cultural explosion and movement. This was a fight for civil rights on a different front: through the creation of first-rate literature and art. This differed from the political action represented by socialist A. Philip Randolph and nationalist Marcus Garvey. Yet the cultural products of the Harlem Renaissance were always infused with political themes and content, representing the resistance consciousness of Du Bois and, more importantly, millions of Black Americans.

The key literary and artistic figures of the Harlem Renaissance have properly entered the American canon of cultural greatness. Poets Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Angelina Grimké, fiction writers Jean Toomer and Zora Neal Hurston, essayists James Weldon Johnson, E. Franklin Frazier W.E. B. Du Bois, and Arthur Schomburg, among others, contributed to Locke’s anthology The New Negro. The Renaissance visual artists also made enormous contributions. Venerable figures including Aaron Douglas, Meta Fuller, Augusta Savage, Palmer Hayden, William H. Johnson, Archibald Motley, James Van der Zee, and others are now likewise widely recognized in American art history.

Gates deals effectively with the intellectual conflict during that era between Locke and Du Bois. Locke insisted art and politics were two separate species. Du Bois correctly thought that this was absurd, viewing all art as propaganda, and must be for the advancement of the Black population. He used his own voice in the magazine Crisis to advance his view that art and culture must be combined with a political vision.

Alain Locke’s view, pervading the Harlem Renaissance as a whole, encouraged Black artists to look to Africa as a chief source of inspiration for their creativity. Closer scrutiny of this view revels that it too is profoundly political, suggesting a basic contradiction to his personal theory. Since the first Africans were involuntarily brought to the Americas, every feature of their African homeland was deliberately cut off, including language, culture, history, and family ties. Even though Renaissance artists could only use Africa as a theme, it was nevertheless an important reconnection and a symbolic political rebuke to white American historical exclusion of their African origins.

Henry Louis Gates offers a sharp and ultimately very perceptive critique in his book of the impact of the Harlem Renaissance. He argues persuasively, I think, that Locke’s The New Negro anthology was launched for the American white educated audience. It would show that Blacks were capable of great artistic achievement and would be a major step in liberating the race as a whole. He acknowledges that the Harlem Renaissance produced scores of writers and artists who together demonstrated a glorious awakening of creativity and imagination. But the masses of Black people scarcely knew of any of this. Gates makes the most incisive observation of his entire book: “No people, in all of human history, has ever been liberated by the creation of art. None.”

He continues by praising what he perceives as a more genuine renaissance: jazz. He chronicles how this original American musical form had deep ties to both black folklore and vernacular traditions. With its root in blues, jazz emerged from the black underground and from the streets of working-class communities. Locke himself was always unsympathetic to the form. Langston Hughes and James Weldon Johnson, on the other hand, wrote much more favorably about this dynamic musical genre.

Still, Skip Gates is correct. Art never liberates people. No art: poetry, drama, novels, painting, prints, sculpture, photography, dance, film––even jazz or any other musical form can liberate any people by itself. I have spent a half century teaching and writing about expressive culture. I have argued, and believe passionately, that politically conscious artworks are integral features of the long and ceaseless struggles for human liberation. They are not merely ancillary decorations, pleasant but ultimately unnecessary. No––the artists who combine exceptional talents with unwavering dedication to social criticism and change perceive themselves as vital parts of the social and political movements that bring such change about.

So Gates’s piercing comment about the limitations of artistic creation should go even further. No people, in all of human history, has even been liberated by the creation of any book. It is humbling, to be sure, to recognize that intellectual achievement too has limited power to change entrenched and oppressive institutional structures. Corporate capitalism does not succumb easily. Its progeny, racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, and related abuses of the human spirit, are pervasive and abound throughout American society.

That dismal reality is scarcely a call to reduce either critical artistic or intellectual work. Quite the contrary: We need much more of both. Stony The Road is an outstanding example; it provides a potent intellectual underpinning for our understanding of the post-reconstruction period. Such historical consciousness is vital for liberation and transcendence.

Political action, however, rooted in a firm intellectual foundation and fortified by equally strong cultural support, can move the day forward. We have seen this in earlier manifestations of civil rights agitation. Without hundreds of thousands of people on the streets in the 1960s, the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed and signed and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was also passed and signed into law. Likewise, agitation by women and members of the LGBTQ communities caused laws to be changed and a measure of equality and dignity restored. Labor, environmental, animal rights, and many other progressive activists have agitated with some successes for their respective causes.

In 2020, the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery have galvanized truly massive demonstration in hundreds of American cities and towns. These have called attention to police brutality and misconduct and to deeper problems of white supremacy. It is the most massive show of protest in a generation, fueled in part by the fascistic regime of Donald Trump. It is too early to know what the effects of all of this collective political agitation may be. Some reforms have already been implemented and even more are in the works. I have been around, and active, since the protests of the 1960s. That long record makes me a little hesitant to think that major changes will result. I remain more hopeful than I have been for a long time. But it is a very stony road ahead.

Image courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California

Photo Benjamin Blackwell. © Betye Saar