[Rabbi Lerner’s note: Hurray for the wisdom of Rabbi Tamares, whose work has now been translated to English by another heroic iconoclast: Rabbi Everett Gendler. Please read the whole book, which will soon be available. The author of the introductory essay below and the interviewer is Prof Alan Brill, Cooperman/Ross Endowed Professor in honor of Sister Rose Thering at Seton Hall University, NJ. The interview first appeared on Alan Brill’s blog “Book of Beliefs and Opinions” with a direct link to the original article. A copy of the original article is also included below.

[Rabbi Tamares has a critique of the kind of Zionism that he saw emerging early in the 20th century, particularly its failure to take seriously the command of Torah to love and respect the geyr/stranger/Other. It is this critique which is foundational to Tikkun’s stance in our Summer 2020 issue that Israel is not a Jewish state but rather a state with a lot of Jews, but not embodying central Jewish values. Its failure in that respect is one of the foci of the repentance we will be doing at Beyt Tikkun high holiday services, along with repenting for all the damage we, the human race have been doing to the environment and to each other to the extent that we have been shaped by the values of the capitalist marketplace, its selfishness, and its various forms of racism and domination. (We invite you to join us for Our High Holiday experiences for which you can register in the third week of August and thereafter at www.beyttikkun.org.) Meanwhile, please read the interview with Rabbi Everett Gendler’s translation of Rabbi Aaron Samuel Tamares and the introductory article by Prof. Alan Brill Cooperman.]

Introduction by Prof. Alan Brill Cooperman

The early decades of the twentieth century were a time of great upheaval in the life of Eastern European Jewry. The overthrowing of the Tzar, the Russian revolution, WWI, pogroms, poverty, and plagues left a Jewry bereft of the old but without a replacement to a new modern form of life. In this time period, we find fierce debates in the Yiddish (as well as Russian and Hebrew) journals. The Orthodox rabbinical world was alive in discussing socialism, civil rights, anarchism, Zionism, spiritualism, nationalism, and militarism. Much of this Rabbinic debate is not well known. One of the important figures in these debates was Rabbi Aaron Samuel Tamares (1869-1931), a near contemporary of the better known Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook. Rabbi Tameres studied in Volozhin Yeshiva four years after Rav Kook and was one of the greats who studied at the Kovno Kollel. He was asked by Rabbi Hayim Tchernowitz to head the Religious Zionist Yeshiva in Odessa which he declined.

Rabbi Tameres attended the fourth Zionist congress in 1900 and started his slide away from political nationalist Zionism seeing it as just another form of materialist political machinations and self-justifying violence. He became a life-long pacifist preaching that the way of Torah is ethics, peace, humanism, and spiritual growth. According to Tameres, “for us, the Jewish people, our entire distinctiveness is the Torah and Judaism; the kingdom of the spirit is our state territory. Tameres called himself “the sensitive person” who feels the pain of the world.

Tameres was the emblematic image of the rabbi who would seek leniency for the poor widow who cannot afford another chicken or who allowed an elderly Torah reader to not be corrected to save his honor. He called many of his contemporary Orthodox colleagues as “Jesuitical” in that their goal was to use frumkeit as a weapon for the public persecution of others.

Rabbi Tameres wrote a Yiddish autobiography but most of his writings are in the style of a Litvak pulpit rabbi, similar to Rav Kook, interpreting Aggadic statements to make his point. Nevertheless, despite the similarity of form, Rabbi Tameres thinks war is always bad while Rav Kook in his essay on war in Orot wrote that war prunes away the weak and allows others to show their virtue.

We approved the naturalistic outlook… that it throws the primary blame for war upon the class that holds power. For however much the ugly clay of war may be imbedded in the hearts of the mass of people, yet those who busy themselves with this nice material, moistening and shaping it for their goal and bringing it to completion—these are surely “the ruling classes.”

Rav Kook thought secular nationalism will be redeemed in a religious dialectic, for Rabbi Tameres, nationalism can never be redeemed.

From that point on the children of Israel became “political,” and the Torah became merely a kind of constitution, similar to those constitutions from “cultured nations” that we today know all too well: on paper, drafted and signed, but in practice, the complete opposite. Corruption begets corruption. The corruption of the ethical sense, which followed in the wake of the invasion from without by the spirit of “political nationalism,” soon brought them to request that a king be set over them also, “like all the nations surrounding them.

Rabbi Tameres published his essays in the same journals in which Rav Kook published his essays, but the latter is widely known while the passivist approach of Rabbi Tameres has been eclipsed.

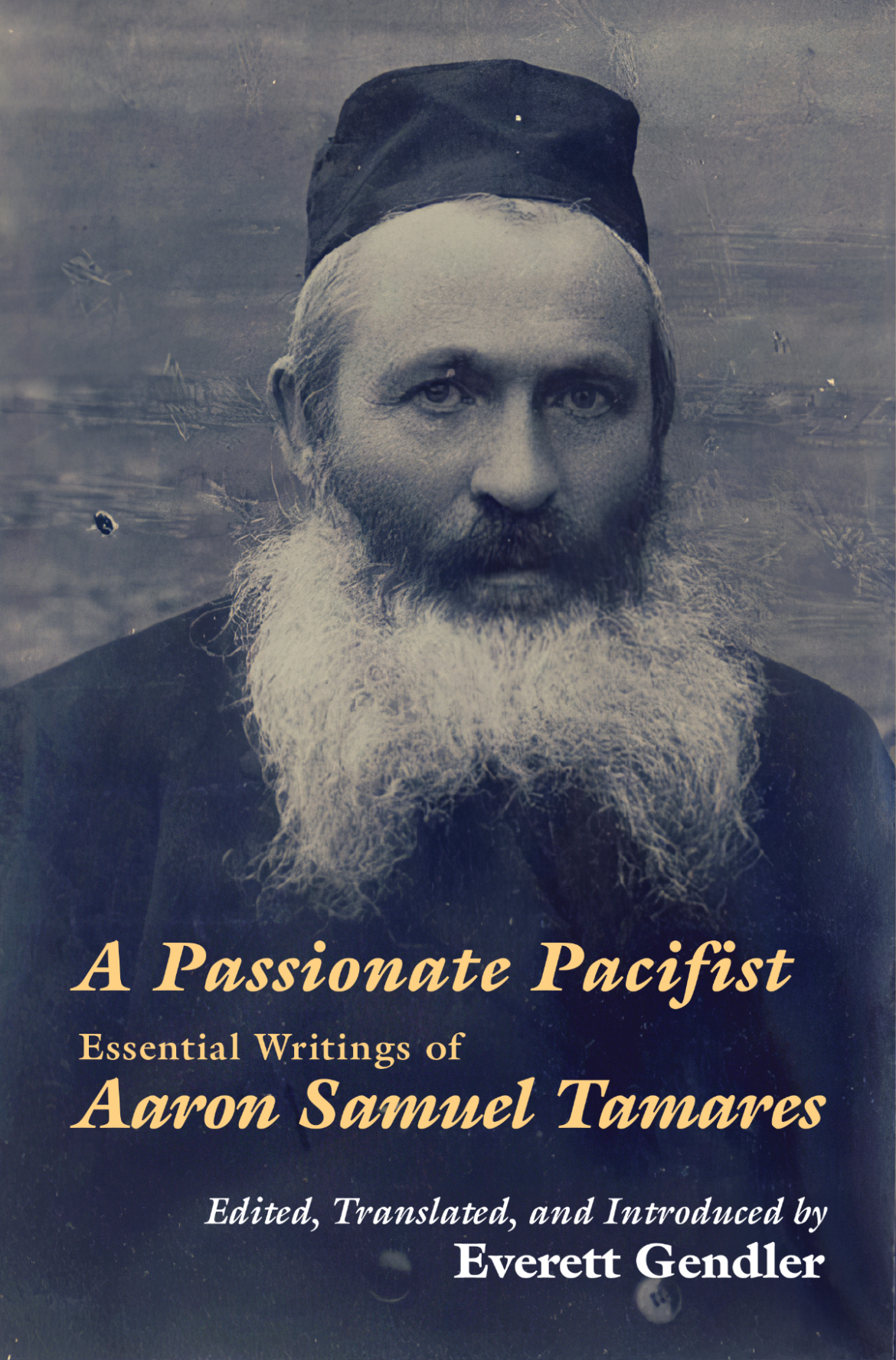

Ehud Luz in his Wrestling with an Angel: Power, Morality, and Jewish Identity translate some portions of Tameres’s writings. We also had a variety of pieces translated starting in the 1960’s by American pacifist rabbi Rabbi Everett Gendler which were widely copied and posted. Rabbi Gendler, who is turning 92 this week, recently finished a project of translating the writings of Rabbi Tameres as A Passionate Pacifist: Essential Writings of Aaron Samuel Tamares, Edited, translated and with an introduction by Everett Gendler (Ben Yehudah Press, 2020) (Amazon) The book is an essential work to understand 20th century Eastern European Orthodoxy and should be read by all those who study and teach Rav Kook. But for those who seek a Torah of compassion and pacifism, a Judaism not tied to 19th century political nationalism, and a vision of Jewish spirituality outside of political thinking this book will be essential. For those sensitive souls, this book will be a source of sermons and classes and inspiration. To those whom I taught some of this work this past week, they found the work offered a chance to personally work through issues on war, politics, and nationalism in Torah since Rabbi Tameres was there at the start of Religious Zionism and his writings articulate issues still alive a hundred years later. The book contains Rabbi Tameres’s autobiography, his early essays and sermons of 1904- 1906 continuing up to his developed thought of the 1920’s.

This blog introduction to the book has two divergent responsibilities, almost as two separate introductions, because the translator Rabbi Everett Gendler’s world is not part of the Volozhin rabbinic elite. Rather, he was the leading voice of American Jewish pacifism, progressivism, environmentalism, and civil rights, for more than half a century.

Rabbi Gendler was the voice of Jewish pacifism since the Korean war. During my childhood, Gendler was on the radio and in the newspapers as the Jewish voice of non-violence. (his articles) He was also deeply involved in the civil rights movement since the mid-1950’s, During the 1960s, he played a pivotal role in involving American Jews in the movement, leading groups of American Rabbis to participate in prayer vigils and protests in Albany, Georgia (1962), Birmingham, Alabama (1963) and Selma, Alabama (1965), and persuading Abraham Joshua Heschel to participate in the famous march from Selma to Montgomery (1965) Gendler was among the founders of the egalitarian Havurah movement and he is the “father of Jewish environmentalism”.

Gendler was involved in changing our society with his colleagues -Martin Luther King, Abraham Joshua Heschel, and Thomas Merton. Gendler was instrumental in arranging Martin Luther King’s important address to the national rabbinical convention on March 25, 1968, 10 days before King’s death, conducting what was to be the final interview with MLK. There is much archival material about Gendler online. Even in a quick search, I found that he wanted to create a Parliament of World Religions together with Rabbi Mordechai Kaplan in the early 1960’s. There is a 60 page archival interview with him as one of the founders of the Jewish counterculture. Much of his environmentalist essays are available online. His 400 pages of collected essays Judaism for Universalists came out five years ago.

Rabbi Everett Gendler earned a B.A. from the University of Chicago in 1948 and was ordained as a Conservative rabbi by the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City in 1957. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Rabbi Gendler served as rabbi to a number of congregations throughout Latin America – including in Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, and Havana, Cuba. In 1962, he became rabbi at the Jewish Center in Princeton, NJ, where he remained until 1968.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Gendlers were involved in several alternative residential communities, including Centro Intercultural de Documentación in Cuernavaca, Mexico (1968-69), and the inter-racial, inter-religious living center Packerd Manse in Stoughton, MA (1969-71). In 1971, Rabbi Gendler became rabbi at Temple Emanuel of the Merrimack Valley in Lowell, MA, and in 1977, he was appointed as the first Jewish chaplain at Phillips Academy, Andover as part of a Catholic-Protestant-Jewish “tri-ministry.” He remained in both of these positions until his retirement in 1995.

Following “retirement” together with his wife Mary, they became involved with the Tibetan exile community which had followed the Dalai Lama to India. At our suggestion, and with his blessing and supervision, we spent good parts of the next 22 years helping the Tibetans learn more about strategic nonviolent struggle. This involved many trips to India, where we conducted seminars and workshops for Tibetans all over India.

Unfortunately, the disparity of worlds of translator and author shows in the work. Gendler’s comments and discussions in the book all concern Gandhi’s thought and his own American life of pacifism and progressivism. These comments are definitely interesting and worthwhile but far from the Yiddish debates of Volozhin graduates after the Tzar is overthrown. However, a scholarly annotated Hebrew edition of Rabbi Tameres is coming out later this year by the experts in this time period Hayyim Rothman and Tsachi Slater. The former has a forthcoming book by Manchester University Press on anarchist Orthodox Rabbis who were reading Tolstoy including Tameres but also dealing with Abraham Yehudah Khein & Yaakov Meir Zalkind. The latter has written a PhD on Rabbi Shmuel Alexandrov, who most only know through his Buddhist Schopenhauer inflected letter to Rav Kook. The world of Rabbi Kook and Tameres was awash in Yiddish translations of contemporary philosophical works – including Tagore and Tolstoy, and this erudition added to clashing views of each other’s essays.

In the meantime, buy this edition (amazon) and read it for its vision of Torah. As he wrote in his Passover sermon of 1906.

We can see difference between the methods of “taking one’s freedom” of the European political parties, and our way of achieving freedom. They took freedom, for example, during the French Revolution, by “barricades” and by throwing bombs upon some despot or another. And we try to achieve freedom by making a seder, eating matzah, singing hallel…that is to say, by means of repeating on our lips the memory of the freedom of the Exodus, the Godly flame will be fanned within our souls and we will remember His kindness and His actions.

An Interview with Rabbi Everett Gendler, the Translator of Tamares’ Writing

1) What do you like most about Tameres?

Two of Tamares’ winning qualities for me are his independence of spirit and his love of nature.

First, Tamares remarkable independence of spirit. In the late 19th century, when most of his Orthodox colleagues opposed the political Zionism of Theodore Herzl, Tamares supported what he thought was a movement for the liberation of the Jewish people and improvement of its living conditions.

Later, at age 31, Tamares attended the fourth Zionist Congress in London in 1900 as a delegate. He was appalled to find what he saw not so much as a movement to liberate people but a movement to liberate territory. After a year of silently absorbing this discovery, he found the courage to denounce Zionism publicly because he saw that its goal was to be another European Nationalist Movement, rather than follow the Jewish mission of Torah and ethics. This independence of spirit and his fresh outlook you find throughout his writings.

Second, His love of nature. In 1912 he was urged to apply to head as the lead rabbi the major yeshivah headed by Rabbi Hayim Tchernowitz in Odessa. Prominent cultural figures such as Hayim Nahman Bialik were his supporters. Less than half way through the interviews, Tamares withdrew his candidacy and headed back to Mielyczyce to return to his beloved friends, the trees of the forest. Tamares lived literally across the road from the southern reaches of the Bielewieza Forest, the last remaining primeval forest in continental Europe. Thoreau spent one year at Walden Pond; Tamares was a forest dweller for nearly forty years.

2) Are there any quotes of Tameres that keeps you company?

Tamares would not do well in a sound bite civilization. He specializes in overarching phrases, lengthy paragraphs, and embellished prose. Here and there are some of my favorite brief quotable lines. For example

The Jews remember always that their God is the God of Truth and Justice who shattered the yokes of their oppressors. They must plant deep in their hearts absolute faith in the power of Truth and Justice to triumph finally…this idea, when firmly rooted in their hearts, will itself serve to defend them from all violent and lying persecutors.

One other telling quote

Every single human being on the face of this earth was created and endowed by the Lord with the capacity to look after his own life….and to worry about death and perishing; each was created for his own sake. The breath which the Lord breathed into the nostrils of Rueben is for the sake of Rueben. It is for him to live and exist and not be a bloody sacrifice for the sake of someone else.

Finally,

The culture of creation in the Book of Genesis: Life, tangible life, the life of the blood and the spirit, this is the need which must first be sought. The life and secure existence of the individual: these are the basis of life on this earth; from them all comes, and in them all is included!

3) Why does he call himself “the sensitive rabbi” and “one of the passionately concerned rabbis”?

Already by the young age of six, Tamares noticed that he reacted with greater feeling than his classmates to stories of pain and misfortune. He was also captivated by the natural sight of trees and meadows and could not tear himself away from them. He also became aware that he naturally prayed with greater fervor than his classmates. Throughout his life, he also reacted passionately to perceived injustice. When Tamares felt the need for the protection of anonymity in writing some of his denunciation of movements and participants, he chose the pseudonym of the Sensitive Rabbi or the Passionately Concerned Rabbi (the Hebrew term margish has both meanings). He had seen too many examples of other critics in the community who suffered loss of reputation and livelihood because of their unpopular stance.

4) How is Tameres a pacifist?

I prefer to call Tamares a Genesis Realist. That is, he proclaims the value of each created human being while at the same recognizing that evil actions occur and imperil our continuing existence. For Tamares, this requires watchfulness and action; the action must respect the human being perpetrating evil even as action is taken. Pacifism is waging war by nonlethal means.

When Tamares talks about absolute faith in the power of truth and justice, I hear anticipation of Gandhi’s truth force (Satyagraha) and Martin Luther King’s unarmed struggle for justice. Tamares was unwavering both in insisting on action (protest, economic boycott and hundreds of others) and insisting that it not be the ultimate indignity of organized warfare. Tamares, similar to Tolstoy, points us toward the remarkable revelations this past century of the power of nonviolent action.see the work of the Albert Einstein Institution, the International Center for Nonviolent Conflict, and Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephen’s Why Civil Resistance Works.

Tamares sees war as the ultimate human indignity. In war, the precious product of creation, the individual human being of flesh, blood, breath and spirit is conscripted without consent and trained to murder a fellow human being. Additionally, valuable resources such as food, scientific inventions, railroads that could improve living conditions for all, are squandered in the mass destruction that is war.

5) What does he think is the task and mission of the Jew?

Tamares understands that the task of the Jew is to strive for a justice that will embrace the entire world.

This is the implication of “I am the Eternal” that concludes the mandate, “You must love your neighbor as [you love] yourself” (Leviticus 19:18). Look toward the Eternal, toward the Source of all existence, the First Cause, and you become aware that you and your neighbor are equal in God’s eyes; that insight validates the commandment. The power of Torah to incline human beings toward the good derives from its putting us directly in touch with the Creator of all, the Source of goodness and generosity, thus rekindling the spark of our Divine awareness.

The prophets, whom he quotes so often, repeatedly emphasize justice, speaking often of economic justice: fair wages, no excessive concentrations of wealth, basic necessities for all human beings. Tamares sees the realization of this vision as the primary task of Jewish existence. Thus the intimate local community must live by these values so that its example inspires others to adopt and live by them.

Tamares sees the global mission of Judaism as creating conditions for full development of the individual human being. This means the purification of life within the Jewish community. Domination of people by others (unjust distribution of wealth, etc,) must be guarded against.

Even a cursory examination of the singular purpose our nation is destined to fill, namely, the purpose of spreading Torah, can cause the hypnotic power of nationalism to dissipate, and we can gaze without fear into the eyes of the nations who are so proud of their territories and monarchies.” Since National Territories have been the cause of mass slaughter, a crucial mission of Jews in the world is to prove, by example, that a people can survive and thrive without a National Territory. There is an alternative to survival by the sword.

6) How is Tameres against nationalism?

Tamares is not against peaceful nationalism; he respects the rights of local groups of people to organize for their common welfare. He supports their trying to improve their living conditions and he recognizes human limitations. People in a defined country have the right to focus their efforts. However, it is that rivalrous nationalism that Tamares condemns, the Bismarck Nationalism as opposed to Liberal Nationalism. Tamares contrasts Bismarck and Junker Nationalism with Liberal Nationalism at the time, and affirms the liberal proclamations of individual human dignity and rights as reflecting the true meaning of Genesis.

7) Why was he against Zionism?

Zionism at the time had many meanings; one of them was establishing a European model Nation State in Palestine as a National home for the Jewish people.

The Balfour Declaration specified that the rights of persons living there would be fully respected. How was this to be achieved? Tamares feared that the European inspired Zionism of Herzl would betray the world mission of the Jewish people, to demonstrate a non-territorial Nationalist model. He was also concerned about the rights of those already living in the land.

Tamares Zionist vision was of a territory inhabited by Jews and Palestinians with no dominating group. He recognized and identified with the historical Jewish connections to the Holy Land. This was to be fulfilled by Jews immigrating to Israel and forming communities that lived harmoniously with others living there. Such a non dominant Zionism is nicely explored in Noam Pianko ‘s Zionism: The Roads Not Taken.

8) What of the traditional attachment to the Land of Israel?

Tamares retains attachment to the historic land of Israel but rejects the imposition of a European Nationalist interpretation on this historic connection. He criticized those at the Zionist conference of 1900 who wanted the Jewish people to be like all the other nations, for him, it was a departure from Judaism’s emphasis on justice. He retains affection for the historic land of Israel, but he rejects the historical imposition of the modern European Nationalist idea in shaping this attachment.

The Jew will always seek to return to Israel and live there; Israel is vital and extant in his memory and in his very veins, it is this Israel which he has preserved in his memory at all times, it is this Israel that he yearns to see with his eyes…. Between this ancient Zionist yearning and the new Zionist yearning lies a chasm of difference, both in theory and in practice, both in the reason for this yearning and in its goals.

The political Zionists yearn for a land upon which our nation shall be “a nation like all other nations”—whereas our people yearn for a land upon which our distinctiveness from all other nations shall be further emphasized…The new Zionism hopes to revive in Zion what ostensibly died in exile: Namely, they wish to create in this Jewish homeland and in the heart of Jews, this coarse feeling of sovereignty, of which they had been divested in exile.

Tameres encouraged Jews who felt personally moved to go and live in the historic land of Israel. He insisted, however, that Jews had a world mission beyond reentering their historic land. Jewish fulfillment of this mission did not depend on establishing dominance in historic Israel.

Tameres understood Exile to be not punishment but purification. In addition, the Jewish mission is unlike the mission of the nations “We must reveal to them that between our world and their world lies a deep and terrible chasm…The means to achieve their success is the sword, whereas as ours is the book—ours is the study of Torah. The nations who don’t have the Torah cannot cast their swords aside.”

He argues that the experience of dominating sovereignty in both the first and second ancient Jewish Commonwealths showed the necessary corruptions of commonly understood National Sovereignty. Therefore, connecting attachment to the historic land of Israel with modern European Nationalism was a modern invention not dictated by tradition.

9) What was his view of the messianic age?

Tameres understands the Messiah as “a term for the redemption or liberation of the spirit of humankind for the expansion of ethical awareness and the knowledge of God in the world.”

He further associates this with Isaiah’s vision that “nation shall not lift up sword against nation” and “the whole earth shall be filled with the knowledge of God.” Tamares messianic vision is a world in which no human being exploits or dominates another human being, where human beings cooperate that all may share equitably the fruits the earth, and where the organized mass murder and destruction of war has been ended.

10) Have you had any second thoughts about any of his many ideas?

How would Tamares have reacted to the unimaginable nihilistic destructiveness of Nazism? Would he have supported a Nation State especially as a haven for persecuted Jews? It is a haunting, unanswerable question.

Despite this, is he still relevant? More so than ever I would argue. Tamares’ cautionary words, uttered more than a century ago, about the problems of settling new arrivals amidst people already living in the land, were constantly relevant and constantly ignored. His warning that place of refuge might become place of domination over others is the very specter we confront today.

11) What is your advice for younger progressive rabbis who work among colleagues in the mainstream who generally are not progressive?

In the late 1950’s, I felt somewhat isolated as a conscientious objector to US participation in the Korean War. In the 1960’s, for several years I experienced warm camaraderie in the civil rights struggle. By the end of the 60’s isolation returned when my relief at the survival of Israel during the Six-Day war was accompanied by alarm at the consequent conquest and spirit of domination. I’ve come to recognize, accept, and appreciate my marginality, and on reflection find that my childhood experience of being one of only three Jewish families in a small Iowa farm town of 5,000 was excellent preparation. Over time, I became increasingly involved with the Reform Movement, but again I feel both mainstream and marginal. But that is probably true for any of us.

My advice for younger Rabbis is to try to clarify your vision, then live it. What lies ahead is a marathon, not a hundred yard dash, and none of us has perfect vision or adequate answers. Pray for the right combination of humility and courage, and plunge ahead in this great, marvelous adventure we call human life on this God given planet.

12) What do you see as your greatest achievement as a progressive pacifist rabbi?

It’s too early to say. I might hope that I contributed something to enhance environmental awareness and engagement within the Jewish community, including in the life of prayer. I might also hope that the practical political potential of active non violent struggle is a little more widely known because of my involvement with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and with the Dali Lama, but it’s too early to know. I’ll not be here for a more definitive assessment, so I’ll resist the temptation to calculate and instead try to keep on living.

Now, still blessed with the precious gift of life and some remnant of wit, albeit with diminished energy, I was able to focus once again on the seminal writings of Rabbi Tamares, a cherished companion for over half a century. Truly ashreni, ma tov helkeini, how fortunate am I, how goodly my portion.