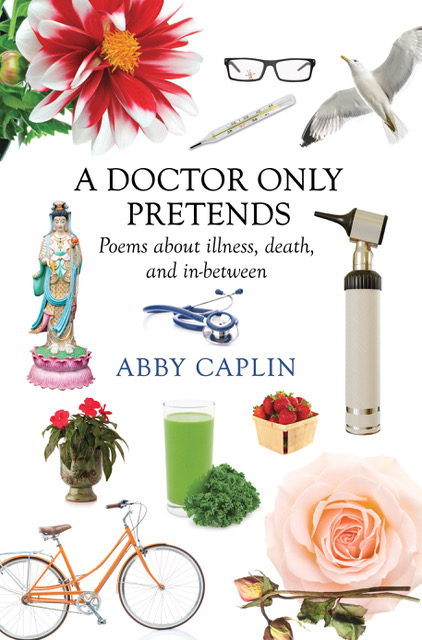

Abby Caplin’s new collection of poems, A Doctor Only Pretends has nothing to do with pretending and everything to do with music. I am not talking about the music of Beethoven or Drake, Omar Sosa or Maria Callas. I am talking about the music of medicine, of what it means to inhabit that professional space—to be human and God-like at the same time, perfect and flawed. Caplin explores both polarities and then the space in-between the two. What was it like to be a doctor before the pandemic? Then, to be in one in it? And now, of course, two years later, processing what? Burnout? Rage? Exhaustion? Love? These poems are that pop song and opera. They are a concert hall packed with patrons and they are the concert complete, basking in silence, listening.

At the center of this collection is a poem entitled “Meditation Workshop,” that begins “Watch my mind barrel down a side trail,” and concludes, “a feather marking the air like a maestro’s baton.” In between these two lines we get to see the poet’s musicality of spirit, a celebration in half-notes and minor scales of the daily encounters of an MD—the toddlers clinging to bedrails, a woman in bed having trouble with breath, and the dead, sitting in chairs, smoking cigarettes. This is a book that celebrates not only the mellifluousness of notes but how those notes collide and, then, what happens in the aftermath of that collision. It’s the bass drum smashing against the oboe and the guitar splitting into the flute. The maestro here is Dr. Caplin and the way in which she guides these poems into and out of one another to create something close to the human experience as perfectly bridled dissonance.

Here’s the thing about these poems—they create desire. When you read one you want to read another. You want to hear another with your whole body because this is a collection of and about the body, one that whistles and weeps, one that dances and dies only to come back to life inside of itself, whole, with anger and sadness, a political power and a joust into the heart of fear. In her cento poem “Prelude to Pandemic,” Caplin writes:

Forget the way men fall

down inside a lie—

the President has neverowned the rain.

How Satan must love to say

the name of God, must enjoyholding aloft one middle finger.

Hard it has become to heal,

and to hold for your neighborthe hysterical strength we must possess

to survive our very existence.

Damning as it is, the devil flashing the finger at all us, Caplin believes we have no choice but to hop the fence, slide under the doorjamb of the apartment next to ours, to visit our neighbor, to hold our neighbor, to offer ourselves out of this unimaginable plight in order to keep going. Deep in the muscles of these words, lines, stanza breaks, these poems implore us to keep going no matter the sadness of the e-minor missive trickling through the ether.

Inevitably, and most certainly abundant in these COVID-days, even in the face of death, we must continue forward and in our continuing forward we must recognize and we must praise the dead, know the dead, be with the dead as we glide and stumble into the kitchen, the garden, the subway, the Laundromat. Caplin knows this. In her poem “Kaddish Duplex (after Jericho Brown)” she writes:

Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead

doesn’t praise or even mention the dead,or tell you how to pray for your dead.

My father prayed in his laboratory,prayed for sterile test tubes in his research lab.

Some love a spinning centrifuge.Anyone who loves a spinning centrifuge

can hang an IV for twenty years.He set up his wife’s IV for twenty years

the way he sorted and filed junk mail.The way he stopped cataloging junk mail.

The way the cat starved by the heating vent.How it decayed by the heating vent.

For the dead, say Kaddish.

See, at the root of this book is the idea that you have to do the right thing. The right thing. That’s what being a doctor is, at its essence. Sometimes all this means is to listen. Being present in the absence of everything else. It’s the hard stuff. But, at the same time, this book is about just being a person on the earth, experiencing the daily grind. A doctor does not so much as pretend as they do live, like the rest of us. She debunks the divine pedestal that we give to our practitioners. What matters for her, what these poems sing, is that we all must say the prayer, be the prayer, in the daily grind, in the laboratory or behind the counter at Dunkin Donuts or under the chassis of a car changing the oil or hanging a spouse’s IV in the same way we might sort and file junk mail. It’s the daily Kaddish that doesn’t mention the dead because living is too mundane and beautiful and the dead are in both, everywhere. Because only a doctor pretends to be a doctor but we are all doctors. We are the doctors who don’t pretend and the poet is one of us, being present. That is our job so we can heal one another when the difficulty is upon us and it is always upon us. This is Caplin’s message. It’s the beauty of the collective spirit of these poems and we can hear it in her baton as it cuts the air.

There is rest here, also, in this collection of poems. The fermata symbol. The voice that tells the musician, “Hey, hold up. Stay here for a second, extend this chord, catch your breath, let the listener bask in this moment before carrying on.” Caplin knows how important it is to breathe, both as an act of physical survival and spiritual rejuvenation. Her poem “Years From Now,” speaks to the power of the pause.

Near the outskirts of Bolinas, a woman offers me

a small pot of coral impatiens and leads me

into a large retreat house, where I choose a room

that faces cypress trees facing the ocean,

and I curl up in the pillowed quiet.

When she shows me the path to the driftwood

chapel, I find an altar of feathers, bones, shells,

a tall vase of fresh wildflowers, river stones etched

with names warming by the window. In my singsong

heart a campfire lights, where I toast marshmallows,

belt out I Know an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly,

and where a woman waits beside me

with a pot of coral impatiens.

Here we have the speaker—doctor, mother, spouse, citizen—in a period of repose. And in repose what does she do? She sings. Close to the cypress tree and the fresh vase of wildflowers, she sings and it is quiet. The silent space of taking time where Kaddish is sung into the ear of impatiens by the curled-up woman in the pillowed quiet. The breath, the air, the prayer. The force of this book is that these tropes extol all facets of doing the right thing in the face of the unimaginable crush of our daily machinations—pandemic or no pandemic. The poems explore the rubble and rust, the tenderness and finesse of a certain gratitude for simply ‘being here.’ In the poem, “On the Occasion of the Final Anatomy Exam,” Caplin writes, “For our awe in working/the pulleys of your fingers and toes, the indignity/of dissecting your genitalia, we say thank you.” A Doctor Only Pretends is grounded in a voice that sings. It’s lyrical in its sonic quality and it bellows the backbeat of the heart. We want to live when we read and hear these poems. They are as essential as the heartbreak of the IV in the vein and the coastal drive from Big Sur that the speaker takes with her daughter, then, finds herself alone on an empty highway, thinking about a friend with a brain tumor while gliding past a row of strawberries.

Do the right thing. The right thing is to sing. A Doctor Only Pretends is both—the right thing and the song and Abby Caplin is the master maestro. This is a book of love, a song of love, a volume of accession and crescendo that pretends nothing. It says: There are flowers out there. Go pick them. It says: Can you not see/that I am still alive,/waiting to be devoured? Devour this book. It will make you more.