I was recently part of a conversation about Extinction Rebellion in which a few of us were asked whether it makes sense for a movement like Extinction Rebellion to focus on the state. I instantly had two things to say. One was that I don’t see any livable future in which there are states. The second was that none of us have a blueprint for how to get us out of this situation, and this leaves us with a big responsibility to discern, individually and collectively, what we can do to move in that direction even without knowing. This piece is an attempt to unpack these statements and invite all who read this to join with me in this deep questioning. Our future may well depend on finding an adequate answer.

The Function of States

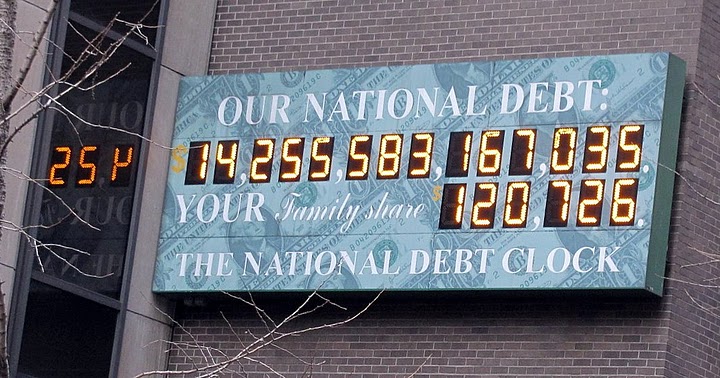

States are a patriarchal invention, not a natural given about humans. They were created early on within the establishment of patriarchal forms. As David Graeber shows in Debt: The First 5000 Years, states, markets, debt, and slavery all come into being more or less at the same time. Their purpose, as I understand it, was to establish control so that extraction from the many to the few could become more reliable.

In part because extractive economies are so resource inefficient, states have tended to grow into empires to be able to amass ever more resources to feed the ruling class and its vassals, and to provide whatever services and welfare to the many, after extracting from them in the first place. Empires inevitably collapse, never imagining that they actually will collapse. So far, those collapses haven’t eliminated the very existence of states. In fact, the proportion of the world’s geography that is organized into states has only grown over time from only a small minority of the world to where now the entire world is divided into states. It’s hard to imagine how we might ever come out of this phase and establish forms of governance that are not based on anything else.

While working on this piece, I did quite a bit of fairly random research on the web. I didn’t find much of what I was looking for. And I did find something I wasn’t looking for: evidence of just how deeply ingrained the idea of the state as a necessity is. Here’s a quote from an article by Harold Perkin, called “The Rise and Fall of Empires:”

The key to the formation, survival and decline of all historical societies is their use of surplus income and resources. Without the extraction, by an elite, of products surplus to immediate requirements – in the form of food, arms, luxuries and other goods and services produced by farmers, craftsmen, traders and servants – no society, beyond the most primitive, would be able to afford the protection, law and order, administration, defence, spiritual advice, personal services, cultural production and so on essential to its existence. This is so obvious that it scarcely needs expressing, yet we know little about the way it arose out of the chaos of pre-civilised experience.

Several things strike me about this quote. One is the near equation of “society” with “state.” In this equation, we are subtly told that whatever isn’t a state can’t be a society. In this, it immediately erases the existence of much of human experience of living and organizing in matriarchal societies which were decidedly not states. This is exacerbated by equating “pre-civilised” experience with chaos. Anyone who takes even a cursory look at the work of scholars such as Marija Gimbutas and Heide Goettner-Abendroth would shudder to hear this extreme negation of our evolutionary past.

Another is the complete acceptance of extraction and of the existence of an elite that does it. Perkin is making it “so obvious that it scarcely needs expressing” instead of mourning that this is all we’ve been able to do, and questioning what we get and at what cost. Looking more closely, as he names the list of what a society needs, the first several are only necessary for maintaining the capacity to extract, and what those from whom so much is extracted receive – “spiritual advice, personal services, cultural production and so on” – appears puny when so much of it could and was available locally in community. As Silvia Federici has shown in Caliban and the Witch, when the capacity of central powers to command extraction diminishes, as it did with the decline of the Feudal social order, the people do not voluntarily continue to make it possible to extract. The fact of extraction, again, “so obvious that it scarcely needs expressing,” is not so obvious to those on whom it’s imposed. It’s the imposition, not something intrinsic to being human, that requires “protection, law and order, administration, defence” for a society to exist. To assume chaos in their absence is to believe certain things about human nature: the core assumptions of western civilization, our current dominant version of patriarchal culture.

The Failure of States

Anyone who, like me, maintains a different belief about human nature then faces the enormous task of somehow demonstrating that a non-state, well-organized, caring for the whole existence is possible. Given the dominance and military prowess of the patriarchal state project, and the immense resources available to the state – especially the modern, so-called liberal democracy version of the state – this is generally a losing proposition. The state can advertise itself as the best game in town with great ease, suppressing or simply not promoting any evidence to the contrary. The same, of course, holds true for capitalism, which, this time, isn’t the focus of my investigation.

Even for those of us who fervently believe in entirely different ways of organizing ourselves as human beings living on a finite planet and needing to coordinate with each other about how, and who see states as inherently problematic, a pathway for a stateless future isn’t obvious. Before moving into exploring what we can do in the absence of a solid pathway, I want to unpack, just a little, what I see as problematic about states.

The simplest version of it is that states were not created to attend to needs or to care for collective wellbeing. They were created to sustain the extracting few at the expense of the producing many. As Perkin himself notes in the article I quoted from, “empires declined because the elites took more than their share of income and resources and paid the price in internal malaise, depression, rebellion or external conquest.” Never mind the notion of there being a share for the so-called elites that is different, bigger, than what the rest receive of the collective pool of resources. The issue remains that when extraction begins, and when the extractors are disconnected from their own care and lose sight of being human beings embedded in a large web of life, little will stop them from continually increasing the rate of extraction to where it goes beyond the capacity of the population and the material base of their state to sustain. Perkin ends his article with great warnings and little by way of a solution short of calling for moderation. It remains entirely unclear who, precisely, is being asked to embrace it. He wrote this in 2002, innocent of all that came since, and died in 2004. I see no evidence that anyone has heeded his tepid call.

This question of how to “moderate” excess extraction now takes two forms. One is about just how much regulation to impose on capitalists. The other is about how much to give back to citizens through various means such as reduced taxation for lower incomes, various and sundry credits, and free services to all or some. In this way, the state is often seen as being at odds with the market. As I have come to understand, the mechanisms of the state are doing the very same thing they are designed to do: modulating the amount of extraction such that the few are sufficiently satisfied with what they have managed to amass and the rest of us can get by sufficiently well that we won’t rise up. Never an easy task.

In all this, the overwhelming majority of us don’t have a say, even with the touted presence of regular elections. When we are invited to go to the polls and elect the next set of rulers, we don’t make the menu; we only select an item from an existing menu. We don’t get to interact with our fellow humans to reach decisions informed by what matters to all of us; we only get to choose within a framework that, from the get-go, was designed against most of us. Collective wellbeing, as I believe indigenous, matriarchal societies understood, comes from collective wisdom. When we act as individuals in adversarial relationships to other individuals, learning how to care for all of us will rarely emerge.

Our Future

I can imagine that for anyone who continues to believe that states and liberal democracies in particular are the best model that humans have created, reading articles like Perkin’s could be anxiety producing. I can imagine this article leaving the reader with serious doubt about whether enough tinkering with the ways of current states, and most especially the biggest empire ever, the United States of America (a name that, for me, maintains the aspirations to rule all of the American continent within it) could produce sufficient reduction in global extraction that collapse could be avoided.

Seeing a future beyond states requires strength and faith. Doing this while, also, holding a picture of a possible global collaboration among humans is even more of a daunting endeavor. At the level of vision, I have shared before about the global governance model that a group I convened came up with, documented here, and, more concisely, showing up in one of my Coronavirus pieces of last year: Apart and Together: Finding Collective Wisdom to Move into a Future for All. It’s an ambitious and detailed blueprint of how we can jumpstart ourselves out of the existing model of nation states and individual participation and into a new paradigm of collective wisdom through literally global and universal participation in decision-making.

There is no linear path I know to get there. There is no linear path to any livable future I can recognize. Does this mean there is nothing we can do? I don’t think so. I see several possibilities, and I am eager for conversations about what else can be done.

The bright side of collapse

The large-scale human experiment I have felt most excited about ever since I first heard about it is Rojava, the autonomous region of North and East Syria. Mostly populated by Kurds, with significant other minorities, Rojava operates in a complex and highly self-reflective bottom-up manner. An accessible summary of the premised and ways of operating of this region can be found here. The experiment has been going on for about ten years now, and self identifies as democratic, feminist, and ecological, and explicitly resists being seen as a state. As far as I can tell, it’s the first ever political entity that is committed to the liberation of all through focusing on the liberation of women. I have alluded to Rojava more than once in my writings, and I am not going to get into any details. The point of referencing it now is simply to say that it likely would not have happened without the partial collapse of the Syrian state. Specifically, the Syrian state is too weak to impose itself on the local population. Rojava, I believe, is made possible within that void. The other large-scale experiment of its kind that I am familiar with happened during the Spanish Civil War, in Catalunya, also a time of state weakness.

Nothing else I know about has operated on such a large scale. And yet there are plenty of stories about how communities and regions that suffered partial, temporary collapse reverted to more collaborative and care-for-the-whole ways of functioning. Even the Coronavirus crisis offers us hundreds of big and small stories about how, when the economy semi-collapsed, communities came together to care for the vulnerable. Not everywhere. Not always. And there are clearly questions to be asked about what conditions support or derail such spontaneous community efforts. Nonetheless, one of the pathways is about staying alert to the growing cracks in the vice-grip of our global economic and political systems.

Connecting the dots in the Commons Movement

While there aren’t many globally visible alternatives, there are endless examples of local communities and other groups, both in the global north and in the global south, that come together and recreate the commons. David Bollier and Silke Helfrich have done an immense service to all of us by documenting and extracting principles from many such experiments and putting the results together in a book they called Free, Fair, and Alive: The Insurgent Power of the Commons. Although continually assaulted by global capitalism, sometimes to full destruction, the reclaiming of the commons continues to happen, and more people are becoming aware of the significance of this movement and its connection to a future. How fast this coming together can unfold, and whether a flexible federation of local commons can be a pathway to replace the state is a big unknown. That communing is essential is no longer a question for me. There is much to learn from, about, and with. All of us can participate at least in the learning about.

Experiments in self-governance

Multiple experiments in self-governance now exist all over the planet, partially overlapping with the commons. All of them started small, some of them have become bigger. Each of us can learn about them. All of them started with some small group of people being brave and imaginative, and taking action. I recently learned about several such experiments, empowering many millions, in India, especially in the state of Kerala, spurred on by one man, Edwin M. John, in collaboration with many. Here are some details:

- 100,000 neighborhood parliaments in the catholic church, each of 30 families, sending delegates to the next level up.

- A few tens of thousands of children’s parliaments, with ministers for climate change, child rights, etc in every parliament, federated up with delegates chosen by a sociocratic election process. The children’s prime minister of India for some years was a blind girl. They aspire for a global parliament of children. Here is a trailer of their documentary.

- 300,000 poor women’s groups, putting their savings together and matching that of a giant corporation, lifting women out of poverty. Federated up two levels to the local government level. Lately, in the local elections, a majority of poor women were elected because of this Kudumbashree project (+ a video). This project involved close to 50 million women.

I met with Edwin, and also read a draft of his upcoming small book documenting the vision and inviting others to begin and experiment in their locales and beyond.

Smaller experiments are many. Here is a small sampling of what I personally happen to know about.

- The town of Frome in England is fully governed by its population, outside any party system. The basic principle is shifting the focus of city governance from politics to solving practical problems. It seems to work, and many are looking to its visionary founders for inspiration in new places in the world.

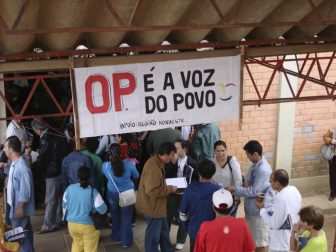

- Porto Alegre, a city of a million and half people in Brazil, led the world in experiments in participatory budgeting that improved health, sanitation, and education and reduced inequality. 50,000 people participated in active deliberation about the budget to reach these results. Unsurprisingly, the experiment failed over time. There are many conflicting ways of making sense of the ongoing experiments, now counting anywhere between 1,500 and 11,000, depending on who is doing the counting, around the world. The core idea of having people participate in deciding how a city’s budget will be allocated remains inspiring and practical enough to continue to experiment with.

- Citizens’ councils and assemblies are proliferating, with various degrees of oomph, ranging from very local to global. There is plenty of evidence that the quality of decision-making and the resulting wisdom in such groups far exceeds what we have become accustomed to.

- vTaiwan is an approach to citizen participation that has become encoded in the law and requires the government to consult with citizens through participatory deliberation processes that utilize sophisticated technology. I haven’t heard of anything like it anywhere else.

Anyone who is determined enough and interested enough can find endless amounts of information. The Co-Intelligence Institute would be my go-to place for starting the search. It’s possible. People have done it. More people can do it.

What are our prospects?

Everything I pointed to in this section is experimental. Experiments like this have lots of vulnerabilities built into them alongside a rich potential for breakthrough. The existing is too dreary. Only experiments might get us anywhere.

As often, I only have questions to end this with, no answers.

- How big would an experiment need to be to achieve actual local self-sufficiency in terms of resources? How far can a group of people reduce its consumption and increase its cohesion and interdependence to actually release dependence on the global market economy?

- How likely is it that an experiment such as Rojava will be “allowed” by the ruling powers to continue to exist before its existence becomes too much of a threat? Whatever we think of Cuba, it’s been under imperial assault for over 60 years. How long can they continue in this lone attempt to do something different before they succumb? Where will sufficient will, vision, and resources arise to make it possible to continue?

In the absence of clear steps and answers, I don’t feel morally able to say to anyone anything about what to do. None of us know what will work or not. Maybe there will be, somewhere, sufficient pressure on some state to move in a direction radical enough, attentive enough to the people, committed enough to care for the whole, that something would flip?

PHOTO CREDIT

US National Debt Clock, NYC (2011-03-04) -Photo by Benoît Prieur on Wikimedia

‘Commons Not Capitalism’ – Photo by Dan Reed on Flickr

UK Youth Parliament, 15 November 2013 – Unmodified image from UK Parliament / Photography by Roger Harris on Flickr

Orçamento Participativo, Participatory Budgeting – Photo from Ong Cidade/Arquivo (via Jornal Sul 21)